TEXT BY MICHAELA MULLIN | VIEW IMAGES

Lianjie Zheng | “The Line is the Beauty”

The line is the beauty of Chinese calligraphy rhythm; it is the emotional change of the time and space.

Within changing temporal and spatial realms of the physical and emotional dimensions, the visual languages of Lianjie Zheng are logographic, calligraphic, and though frequently his brushstrokes may be reminiscent of asemic writing, meaning is always imbued. By Zheng, by audience. By all who breathe. For what Zheng ultimately does when he makes art, be it video, photography, installation, or painting—is to allow energy to circulate, so that strength of spirit is taken in and brought out with each work. And in his paintings, the ink mixes with acrylic mixes with blank space, a positive space that Zheng uses as a medium in itself.

During an email correspondence with Zheng, in response to my contemplation of ink painting and a possible correlation to writing “without meaning,” or the aforementioned asemic writing, he continues:

The line is light and dark, reality and virtual, whether it is layout or structure, it takes a long time to train […] when you do ink painting let your hand hold your brush, your mind control your hand […] to achieve smooth and natural. I put the melody of calligraphy and music into my imagination and painting space. It seems to be meaningless; in fact, it is the reproduce of life energy. Writing in freedom is an important spiritual feature of my paintings. The beauty of the flow line also symbolizes my life journey. For decades, I’ve been constantly discovering and deconstructing myself, a different state of my life give[s] me different new meaning.

In spending time with Zheng’s work, I am reminded of something Leo Steinberg wrote about the mid-century stance shift for both artist and viewer (from the position of the columnar body, as Steinberg calls it, to the idea laid out as if on a flatbed printing press). Writing in 1972, he posited that: “The pictures of the last 15 to 20 years insist on a radically new orientation, in which the painted surface is no longer the analogue of a visual experience of nature but of the operational process [….] What I have in mind is the psychic address of the image, its special mode of imaginative confrontation, and I tend to regard the tilt of the picture plane from vertical to horizontal as expressive of the most radical shift in the subject matter of art, the shift from nature to culture.” [1]

It may seem strange to cite Russian-born American art critic Steinberg regarding style and genre conflation while discussing Zheng, an artist whose work is still often found hanging vertically upon walls, and who confidently states:

I don’t care about the genre. Yesterday I was in Beijing, today I’m in New York. I naturally rejected participating in all type of genre. Art is the way as individual, through their unique visual language, to get communication with the society and audience.

But what interests me is that Zheng is an intuitive engineer of ink-painted worlds, though not in a representational sense. Instead of artist as some form of glass maker, constructing windows/mirrors, Zheng conducts the shape of seeing into paper as a means to see beyond or inside the materiality of art works, ourselves, and the subject/object—even those that subject to oppressive powers or object to them, in search of more peaceful and balanced living. Opacity and transparency create the median or medium of translucency. And trans- is very important in the work of Zheng—transnational, trans-positional, transformative. As is pulse, rhythm, and spirit. For Zheng is vigilant when nuance is at stake, and what is always at stake in his work is the liminal space where skill and effort meet organicism, where control meets what cannot be controlled, and surrenders in the most sublime way.

At his 2018 Walter Wikiser Gallery (New York City) solo exhibit, The Color Between Black and White, Zheng’s work focused on the theme of black and white, because:

Black and white are the opposite color. In Chinese culture, black and white are Yin and Yang. […] The symbol of Tai Chi, in Chinese Taoism culture— that image is black and white [and] In Chinese calligraphy and ink the black echoes the white space […]. Blank [doesn’t mean nothing;] it is a dynamic space reserved for the audience. In Chinese history, different artist of all period, they know how to use black and white as the main subject and power […]

But Yin and Yang are not strictly opposites, of course; one must acknowledge the integration of each into the other. There is bleed—bleed through. Where experience complements experience, where ink brushes, expands, soaks—it reinterprets by interrupting or intervening. The trans- becomes inter-. From moving across and between to becoming together.

Though Zheng immigrated to the US from China in 1996, he currently divides his time between the two countries. This reciprocal and very personal exchange and integration of culture/s has become for Zheng, however, something that is no longer a divide, but is rather more geographically holistic:

My own culture and the American culture I was facing, diverse ethnicity and personal experiences, are integrated into my creations […] I often have a yearning for nature, including the countryside and the vast land of mid-west area, all give me many inspirations just like the Chinese landscape I love. I was going to Mountain Hua twelve times during the past twelve years. Every time I spend a couple of days or weeks, I live with the monk, to [understand] deeper and deeper the real mountain life, to clear my mind. Traveling between China and the US also determines my decisions, like which color I would use and what type of lines I would draw…

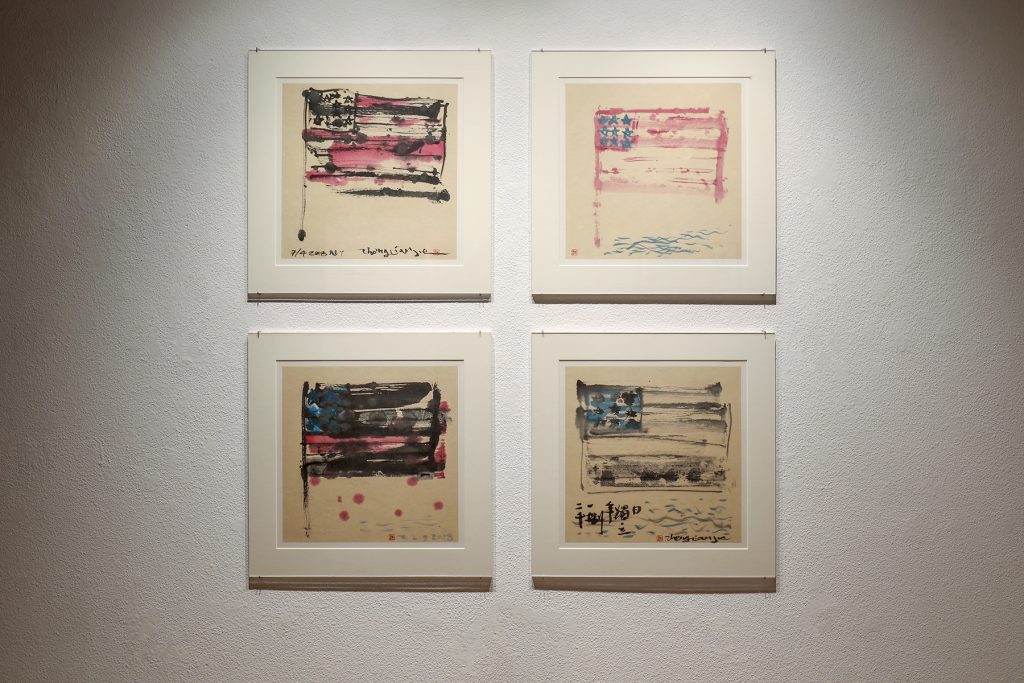

Red, white, and blue and black lines make up the four ink and acrylic paintings which comprise The Blue Field series in this exhibit. Each work abstractly depicts one flag, unfurled, stretched taught, and without wave. Each flag stands high above what appears to be small blue ridges—of water, of land, of air? The movement is here, below, so that the entirety of the piece does ripple. Like Jasper Johns’ Flag (1955) and White Flag (1955), which were painted after Johns Army discharge, and based on a dream of star-spangling, Zheng manages to blend the idea of Johns’ work and Magritte’s “Treachery of Images” (“This is Not a Pipe”) (1929), and to elevate it to one more remove. Zheng loosens the shape with which we are familiar—this symbol of territory staked and for many, home found—and pulls it apart with the brush, diffuses it as an agreed-upon referent.

Zheng’s use of blue and black is also prominent in his Spring in Central Park paintings, where the feeling of place becomes the driving force. Imagination emerges from placement and time of placement. Here are the emotional changes that, like seasons, shift both calmly and furiously, and at the crossing of cold and warm fronts, creates a formidability to reckon with all the short-lived blooming. Even on the densely populated island of Manhattan, Zheng finds the natural:

I’m digging in nature, nature just like a school of the human being […] My paintings are also derived from the learning of nature. My artwork has my expression about our society, history, and present […] The surface is driven by inwardness; the awareness of spirit is in order of Chinese Tao.

But annual and perennial concerns are not on the mind so much in more strictly urban spaces. The Jiangmen Series explores this (as well, this region has many Western influences based on its history and geography). Here, the city is expressed in its most essential form, the sensation of movement within and movement out of and into the space and architecture called city. The Winter of Northern paintings then again take us to the country, lay us down in open land, sense a scape without category or genre. The seasons here are not so much calendrically linear, though the line brings them into being. And the browns and blacks and whites give us momentary frozen or dormant life form.

Because Zheng activates—he paints concept into emblazoned form. And his love of music assists in a conductivity of the cacophonic and harmonic lyrical here writ, inked, and painted. It’s fitting that Zheng is showing again in the Midwest, where the rolling hills of Grant Wood can recurringly become contemporary inspiration for all who experience this middle land, medium of hills and prairie—where Spring in the Midwest is the emotion that centralizes, locates for a moment what Lianjie Zheng is moved to keep discovering—how to embrace and be embraced

[1] Steinberg, Leo. “Reflections on the State of Criticism,” Dancing Around the Bride: Cage, Cunningham, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Duchamp. Philadelphia Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London (2012). Originally published in Art Forum 10, no. 7 (March 1972), pages 44-49.

All italicized quotes are Lianjie Zheng’s responses to questions from an email correspondence between Mullin and Zheng between April 6, 2019 and April 15, 2019.

Michaela Mullin, PhD, is a writer and editor living in Des Moines. Her first book of poems, must, with drawings by Argentinian artist Mariela Yeregui, was published in 2016. She is the Associate Editor for Nomadic Press (Oakland, CA) and arts writer for Moberg Gallery (Des Moines, IA).

Click to view Exhibit Documentation for Inter/national Contemporaries

Exhibit Images

Click to view Exhibit Documentation for Inter/national Contemporaries