OCTOBER 5: ARTIST RECEPTION AND DISCUSSION WITH LAURA BURKHALTER | 1:00 – 3:00

The Politics of Worthiness is the latest exhibition by Teo Nguyen. It consists predominantly of acrylic paintings that depict his birthplace of Vietnam in ways that are picturesque, skillfully done, and somewhat uncanny. Picturesque, due to the landscape genre focus; skillful, given the artist’s attention to the physical scene and the film used to capture it initially; uncanny, on account of the many compositions that allude to a lingering presence between the viewer and the viewed.

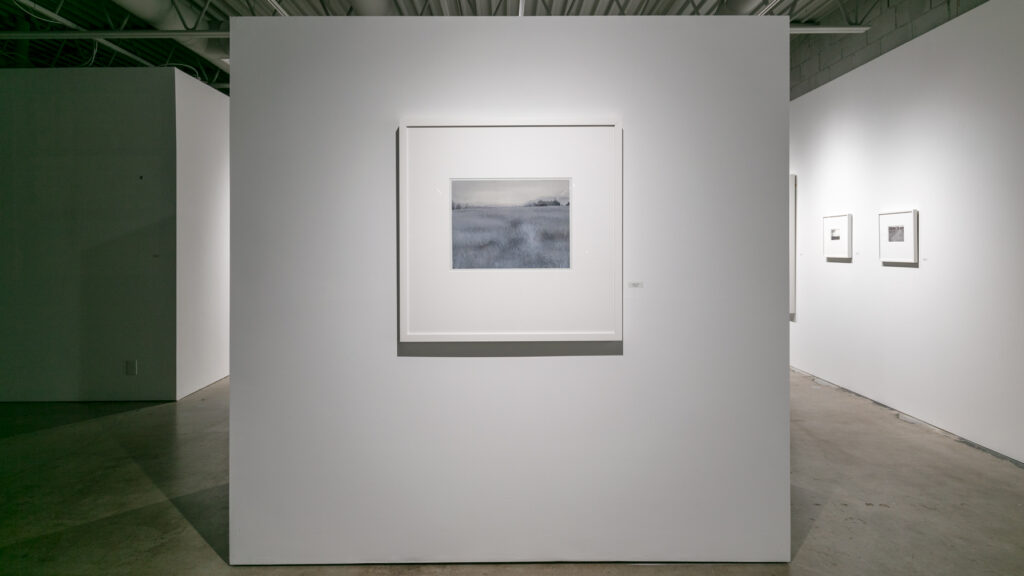

Take “An Afternoon with You, Gone.” Stark demarcations of fore, mid, and background recall the high horizon line. Below are thin, white strokes that pepper the scene as long grass; a dark shroud, as if a cloud or something just as voluminous, passes over them. Above are palm trees that add context queues to the locale; their branches appear caught within a white fog and seem to phase into and out of existence. A mid-tone wash occupies the space between; it looks like emulsion more so than paint, perhaps as a consequence of the vellum surface.

Allusions to film abound in this show because photographs are the reference point. They are photos specifically through the lens of the Vietnam War. While conceptual concerns take precedent, it is through the realm of war photography that Teo finds unique outlets for prior formal proclivities. Articulated as Studio A and Studio B, these previous series explored hyper-realism and abstraction in separate corners. Now, as he works with natural elements and optical distortions together, two arenas become one.

“You are Me and I am You” is a prime example. It’s an abandoned street. A tree shadow looms upon the pavement. The application is somewhat blurred and finds a visual complement in the trees seen further ahead. To the right, buildings are afforded a similar flexibility in their rendering. A lamppost, a business front, a complex of open windows. They are basic shapes diffused into swatches of color. Their soft edges hint at a focal component that, at least in a photograph, might be taken for granted.

The tactility brings attention to the picture and the process of picture-making, wherein a photographer decides what elements to focus on, to blur out, or to neglect entirely. With paint, those decisions have an immediate, visceral effect, one that shocks the senses that have dulled to proliferate, overexposed content. The translation from celluloid to acrylic does a lot of work on its own, but it’s that in addition to careful omissions that elevate the exhibit beyond a formal exercise.

Consider “I Have Traveled a Long Way”, twice repeating. We see at two distinct scales a haze of smoke, some brambles to the right, and stones that punctuate an otherwise dirt enclosure. It’s tempting to marvel at the painting process alone, given how similar these two renditions are and how specific the tool requirements were to accomplish said similarities, but there is an expectancy inside both versions that redirects attention elsewhere. It is a forest with an earthy landing, sure, but upon that landing is a void to both occupy and dwell upon.

This void, this pregnant pause, was once occupied by soldiers. Three soldiers, in fact. Two living, one dead, the latter wrapped inside a body bag. They were visually extracted, alongside other acts of violence, multiple victims, and machinations of war, but their presence was not necessarily removed. The specter lingers while the painter attends to the land and, by extension, to the task that keeps spectacle at bay.

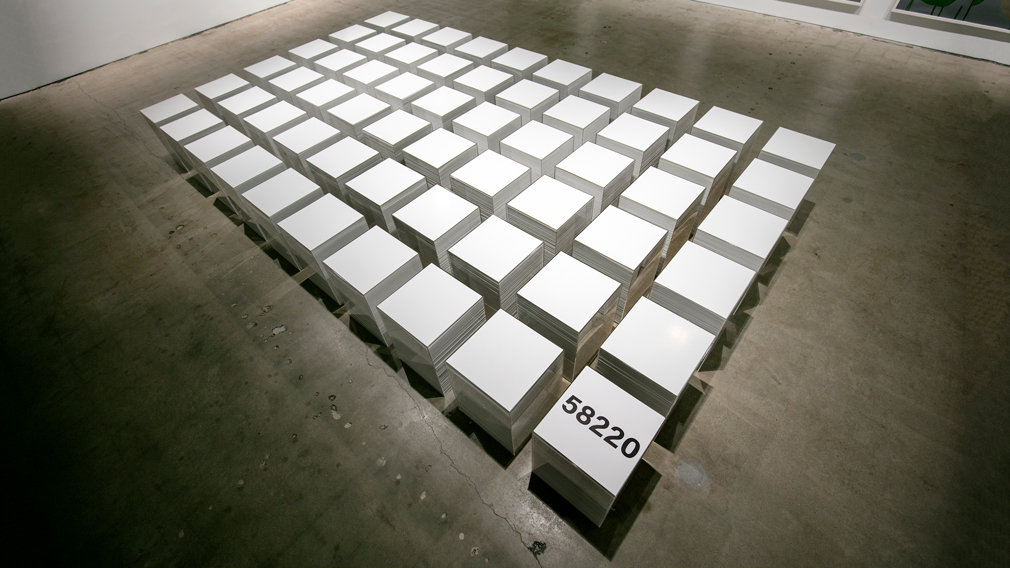

Teo goes about this journey not as a corrective measure, but in an attempt to afford peace. Peace for the nameless casualties and for the natural environment that served only as a backdrop for so many campaigns thereafter. While he has written extensively on this topic, he defines these stakes precisely in three other works present in the gallery. A video, which collaborates with his mother’s poetry to play out a sequence of hardships, observations, and joys that manifest despite those hardships; a sculpture, composed of miniature plinths, each made up of plain sheets of paper that are indicative of the counted and uncounted, that serves as a memorial to all those lost in the conflict; and a 4-frame collection of lotus paintings that act as a vital offering and an example for those who seek to offer similarly. The Politics of Worthiness, by recontextualizing found imagery through the labor of paint and presenting various paths towards acknowledgement and peace, affords us a view and a means to see harm, heal wounds, and move forward together.

View Artworks from The Politics of Worthiness

View Reference Images from the Vietnam War