Text by Nick LaPole

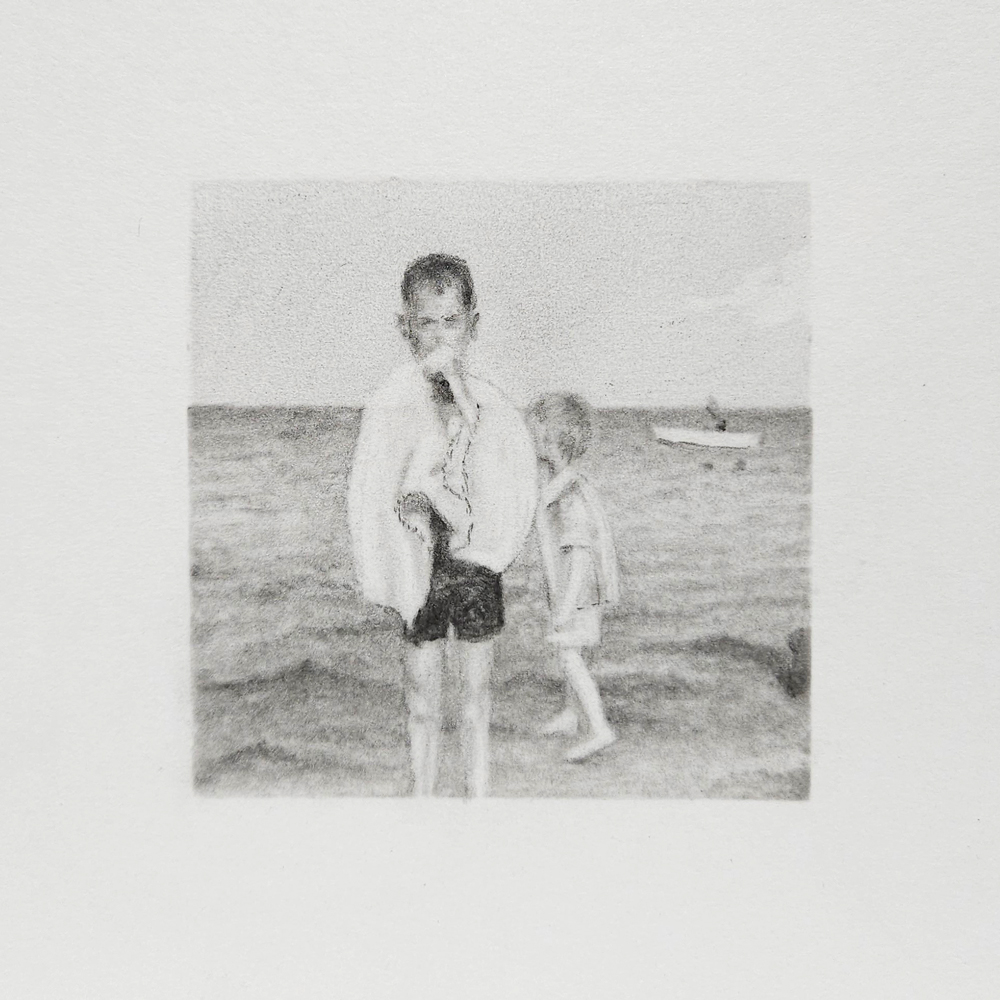

Jeff Fleming’s “Ghosts” are domestic hauntings. They are drawn from his old family photographs, found among yesteryear’s ephemera so often crammed into the attics and basements of childhood homes. Whether they lurk or simply reside inside is a matter of conscience for, regardless, such things are typically forgotten. That is, until a jolt snaps the occupants to attention and rouses them with a myoclonic jerk from a contemporary, spiritual slumber.

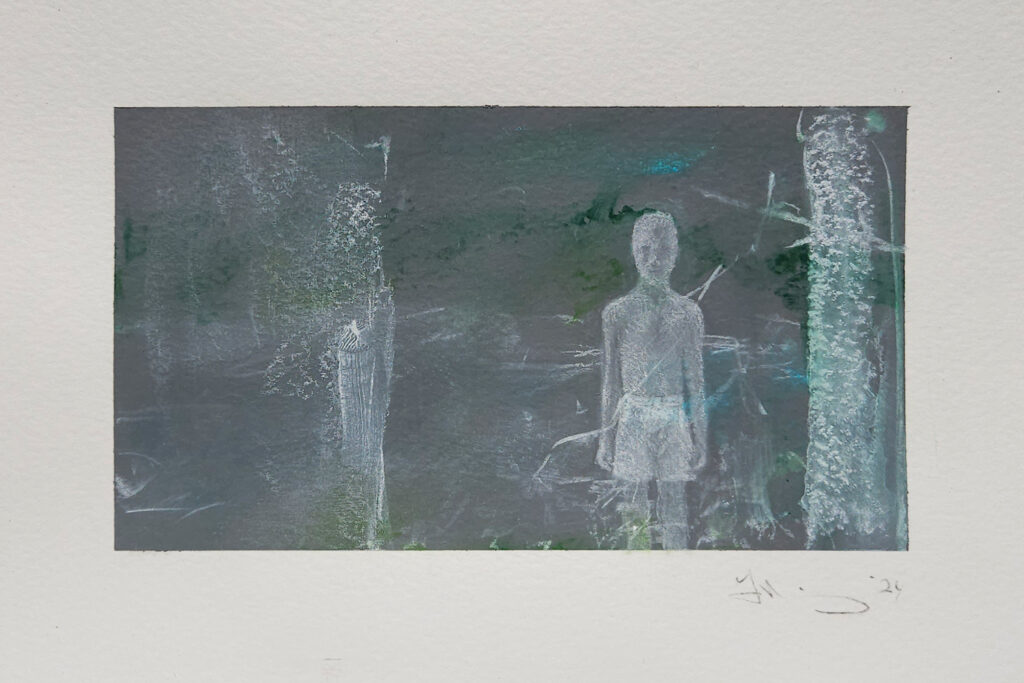

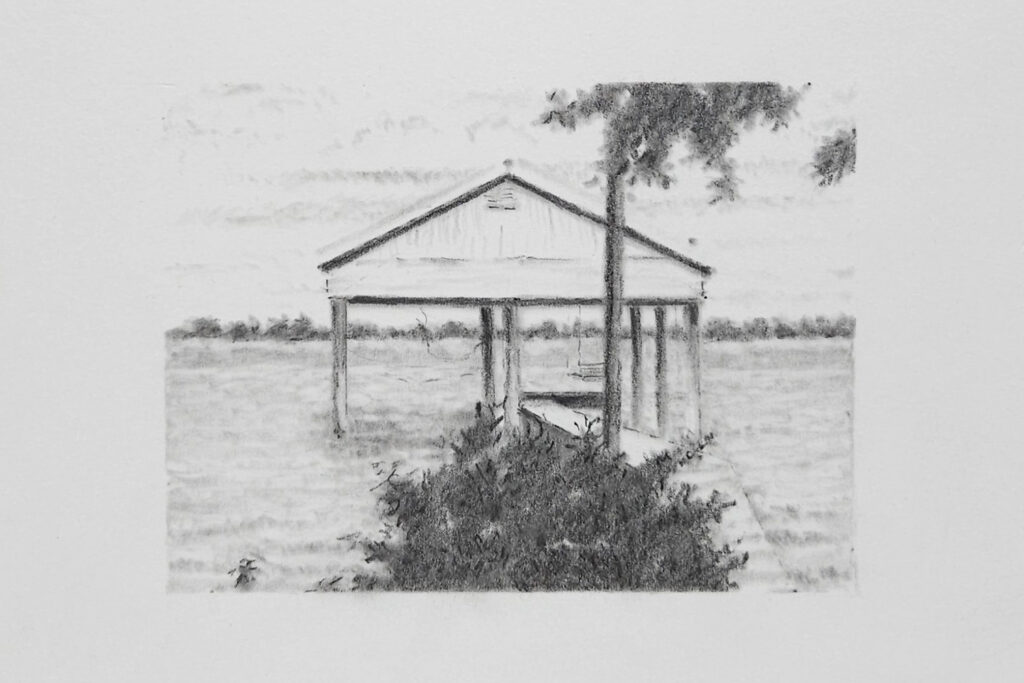

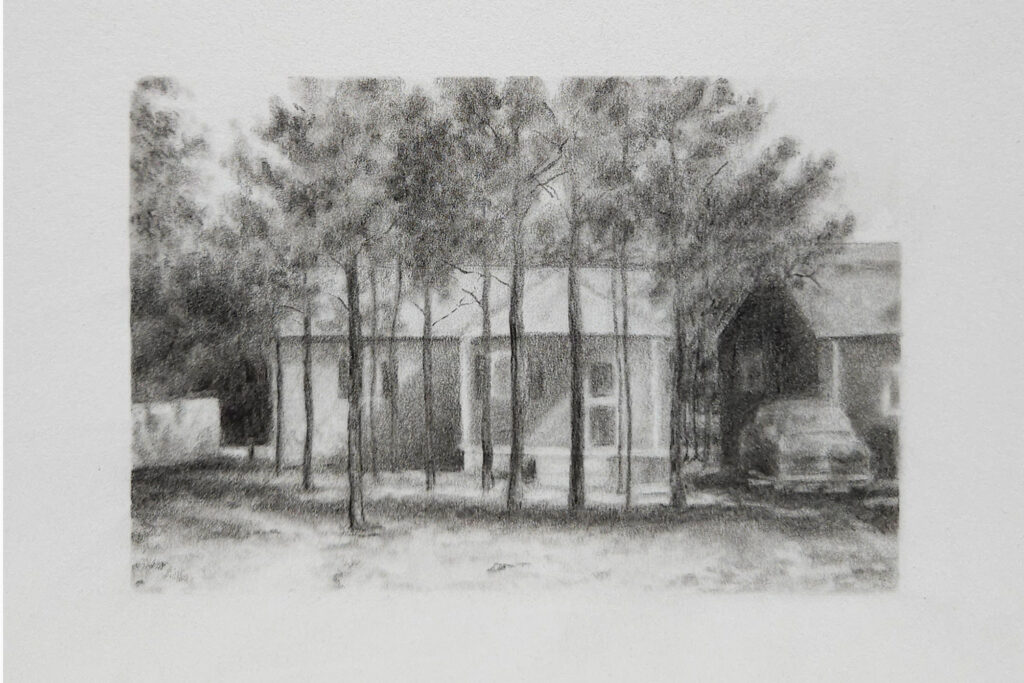

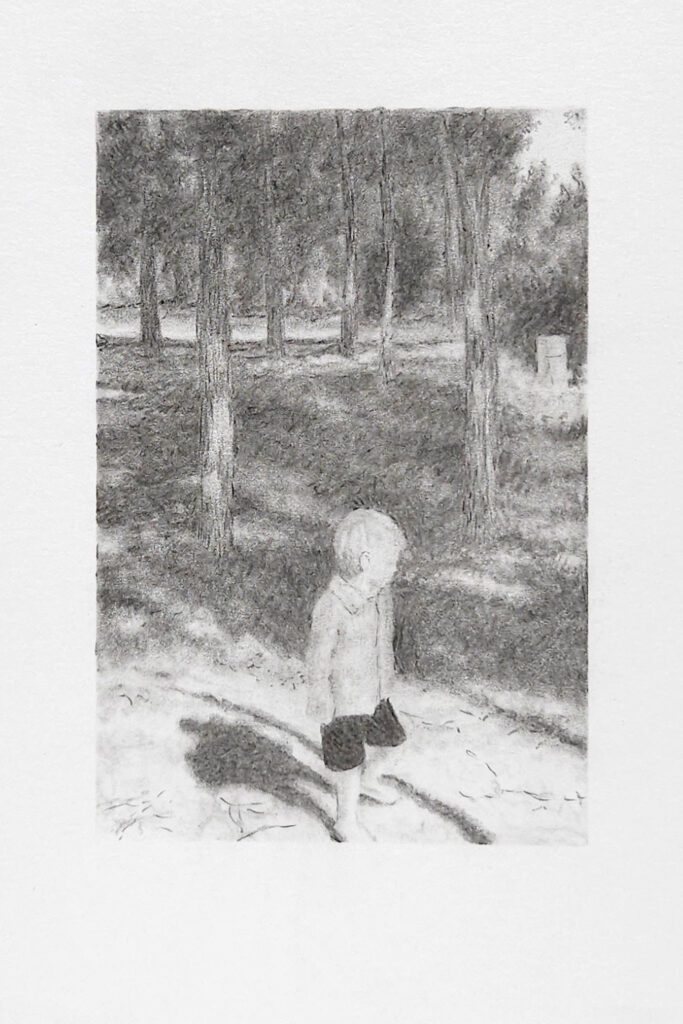

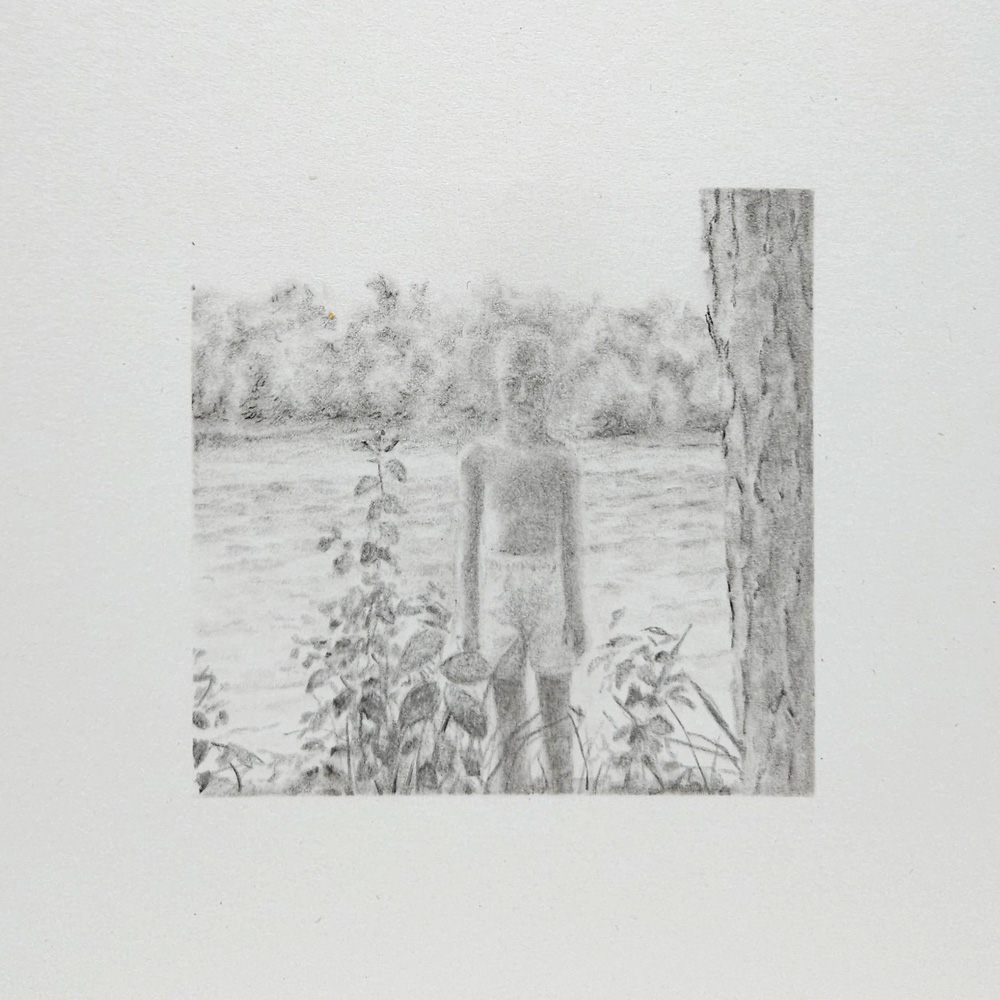

This is how the exhibit begins. The artist sifts through his personal archive and proceeds to the drafting table with recollections in tow. Images of loved ones and personal locales are the primary subjects that are studied and translated into drawings. Pencil on paper, gradations of graphite on white which, distinct from the photo paper origins that wear their age with discoloration, appear here faint and doggedly out of time, as if observed through a fog of memory.

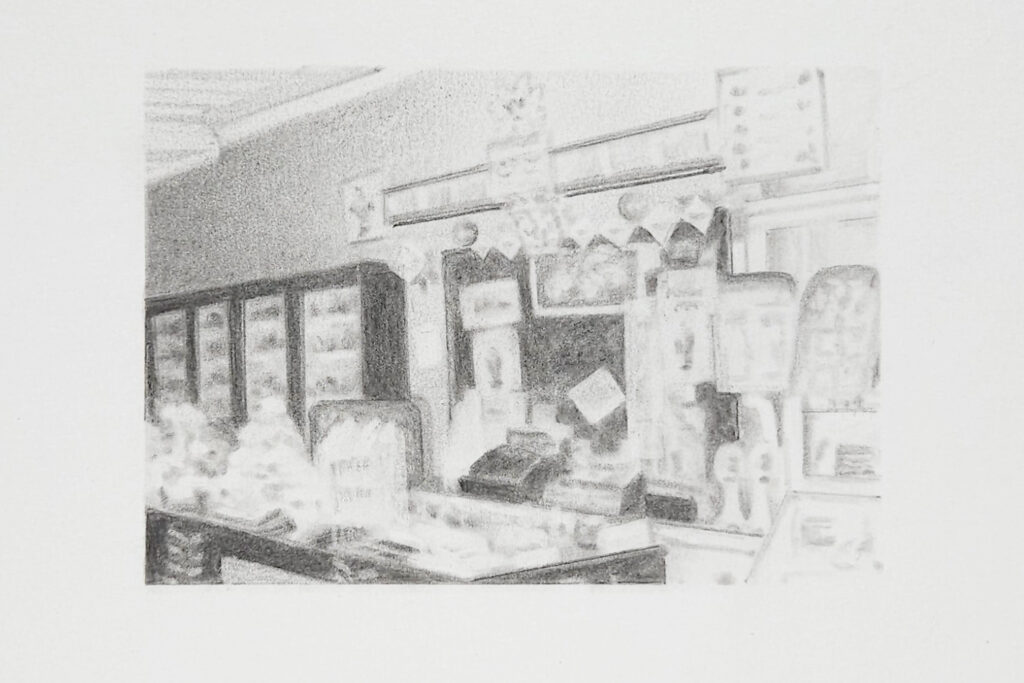

“Drugstore” is one such venue that emerges from the haze. Traditionally, it is a place enmeshed in the context queues of the era. Brands, products, and flyers exist alongside the localized paperwork that tends to clutter up countertops. This drawing defies convention, however. Signifiers are withheld and replaced by gradation, which affords the shape but not the name of a multitude of things, whether they be items or sentiments. What holds sway, then? When name, declaration, notice, or slogan are lost and only graphite static remains?

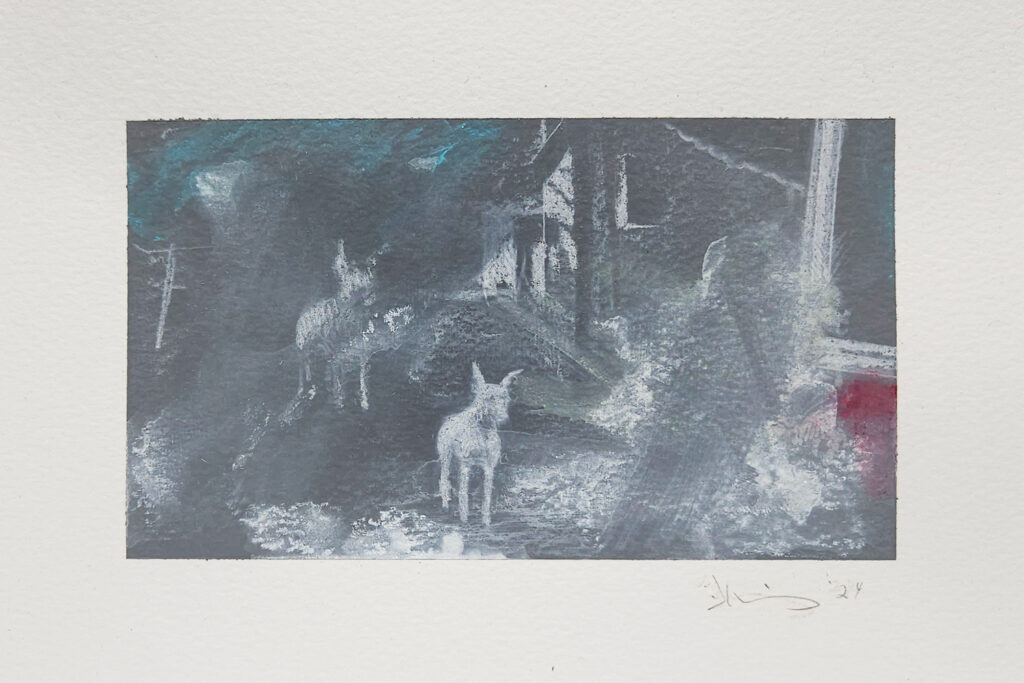

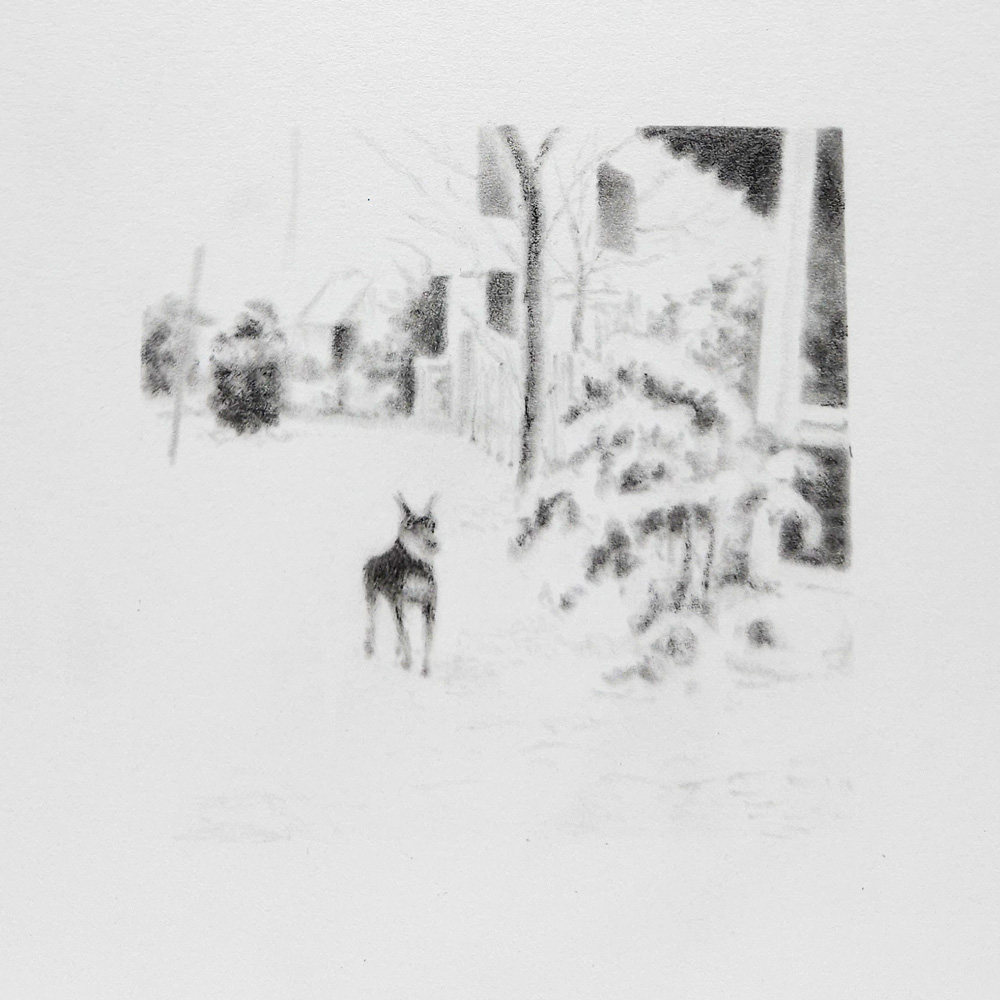

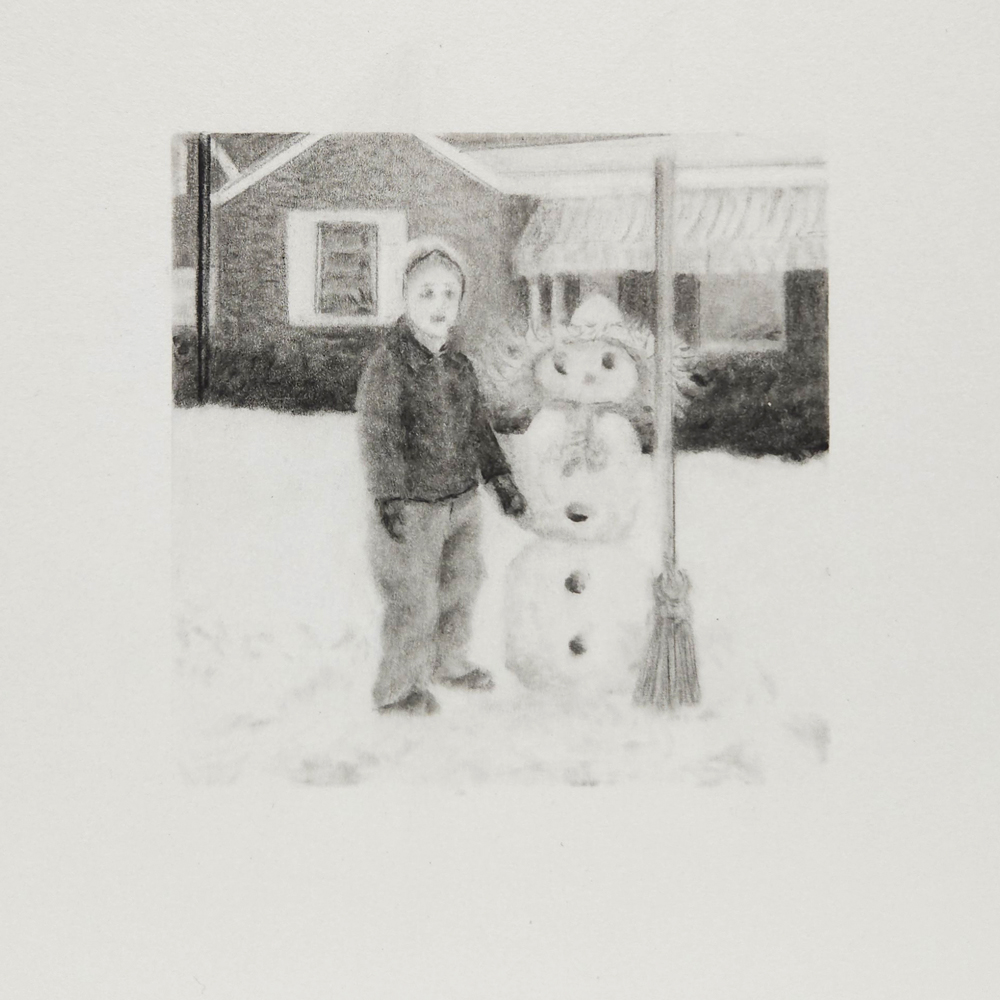

Consider “Topper/Snow.” The page pulp and snow fluff are synonymous here, and so too are the subtle blends that define the brush, fence, trees, and Topper himself. All become one amid the softening of time. The artist parses the scene gently with their hand; the eye of the viewer must parse it gently, also, in order to make out an otherwise slippery circumstance. Is the yard boundless now, with its celluloid borders effaced? If that’s the case, where will this good boy go? What better memorial to our previously collared pals, to relationships sorely missed, than freedom.

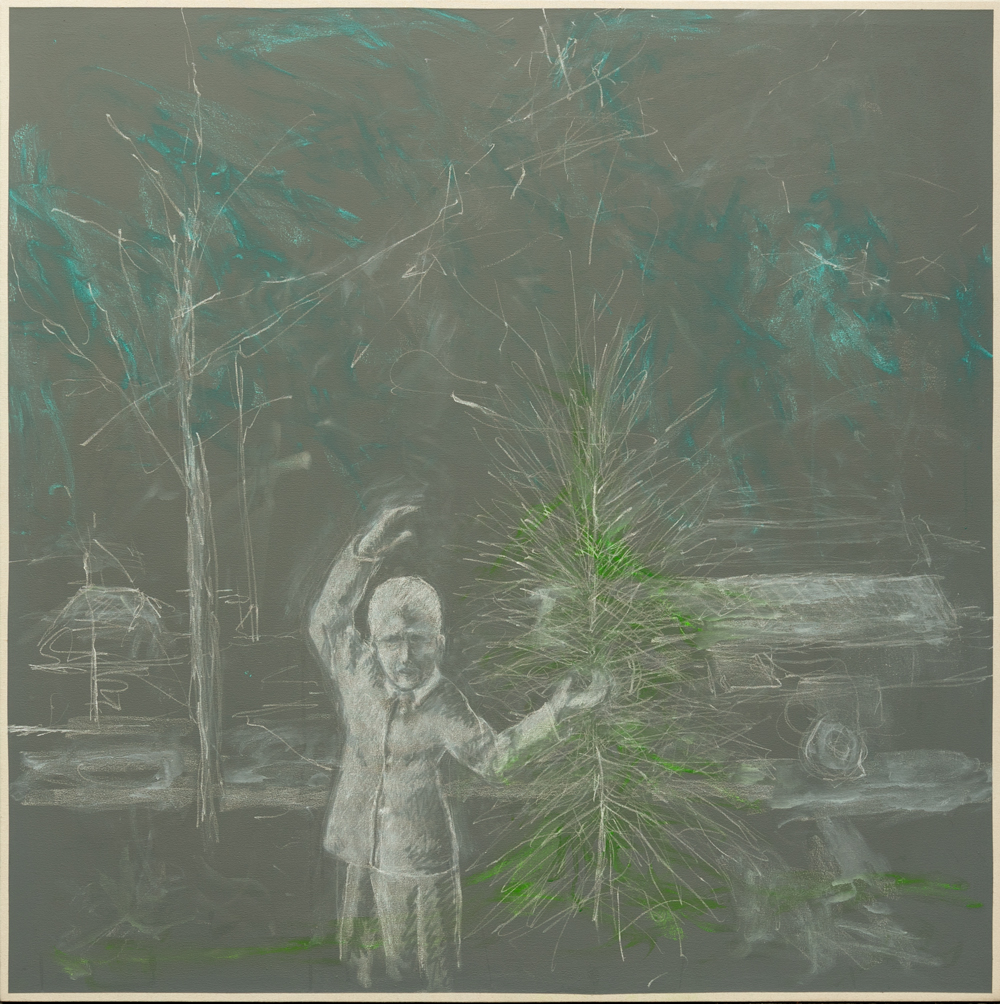

A picture made soft is elusive; to be elusive is to be fleeting; to be fleeting is a half-step away from true freedom, where subtleties manifest as a blur. Reminisce and rediscovery merge together as the artist endeavors to render a picture. While fears associated with time’s passage, memory lapses, and bodily failures may persist in any reading of the past, Fleming continues on and excavates what is visible. From there, he applies these selections to a framework alongside the tactile evidence of the drawn process. The resulting depictions are chalkboard scrawls composed of pastel pencil, India ink, and white charcoal, with several iterations that hint at the malleable surface of our present moment, one composed of erasure, build-up, and endless juxtaposition.

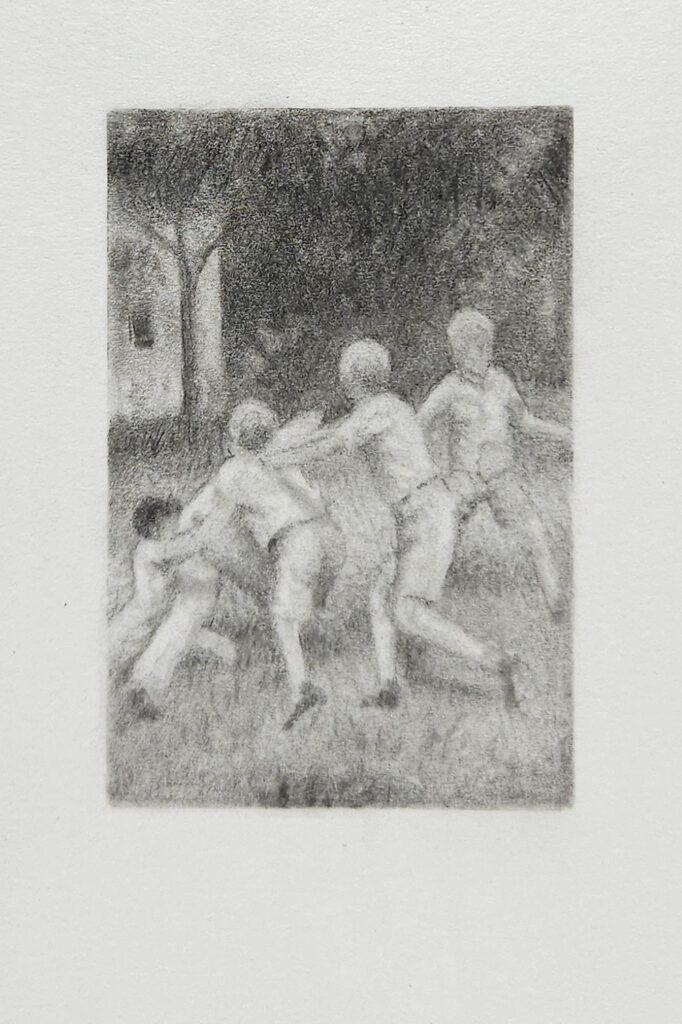

One such derivation begins in “Football,” a collection of two images. In the first, brothers or friends are at play. It is a roughhouse portrait. The principal players are engaged in a scrum upon an area of turf just shy of nearby houses and foliage. It’s a graphite snarl back there, with tree sinews and a distant window smudged into view. One boy, half engaged yet posed in anticipation, looks to the right, as if looking out to passing adults for permission to continue or an admonishment to cease entirely.

The next iteration leaves that historic yard and enters the liminal region of the chalkboard. Here, “Football” ditches the camera lens restrictions, expands the surface area, and squares things off. Synapses of green, blue, and yellow fire off alongside the principle players, a band of brothers whose outlines echo periodically up the picture plane. While energetic as ever, they are less of a tussle and more a unit. They may in fact be one in the same, for each share a similar, tightly bound chalk frenzy that informs their body.

It’s the recapitulation that gives this exhibit power, for rather than dwell on the past as a static entity, Fleming brings its myriad signifiers into the present. This offers both himself and the subjects an opportunity to live in ways unassumed, in conditions unanticipated. Passive nostalgia is reconciled within the active endeavor or artmaking. While missed connections and regrets manifest amid the reminisce, “Ghosts” beckons us to proceed onward alongside our countless retrospections.

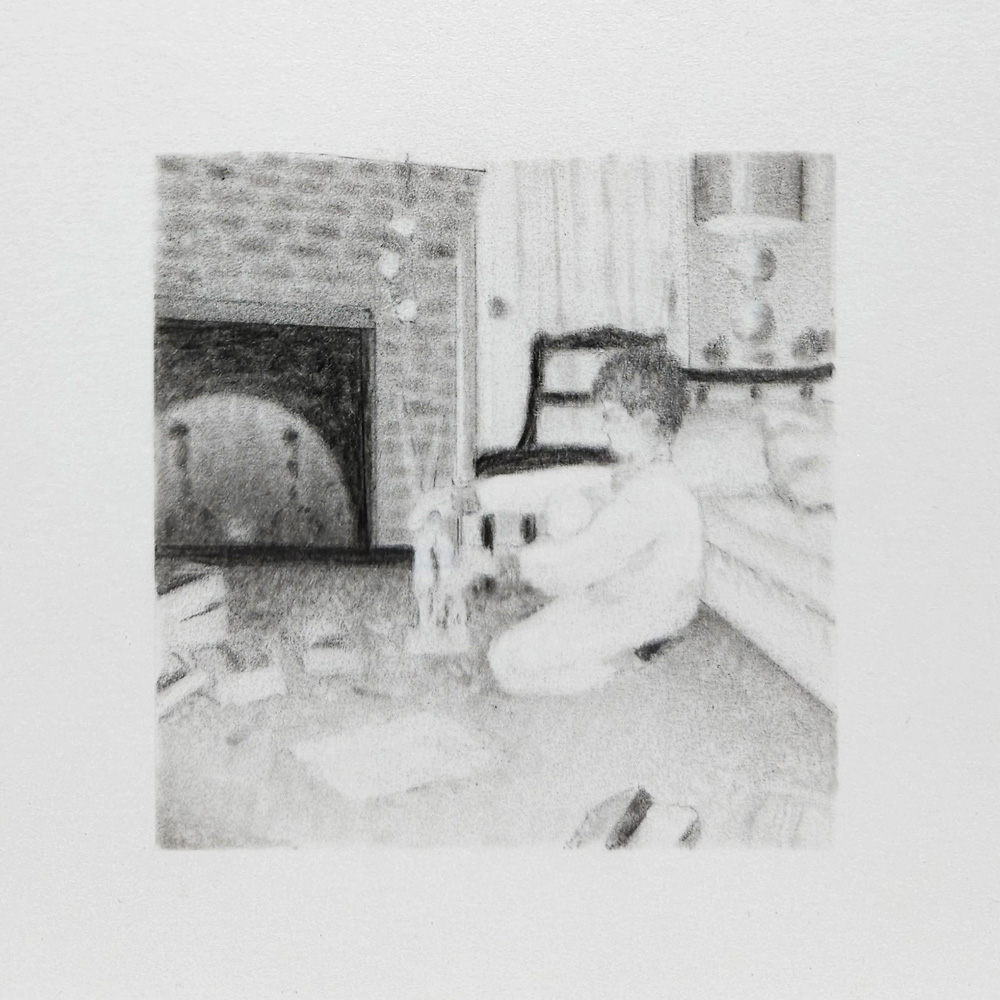

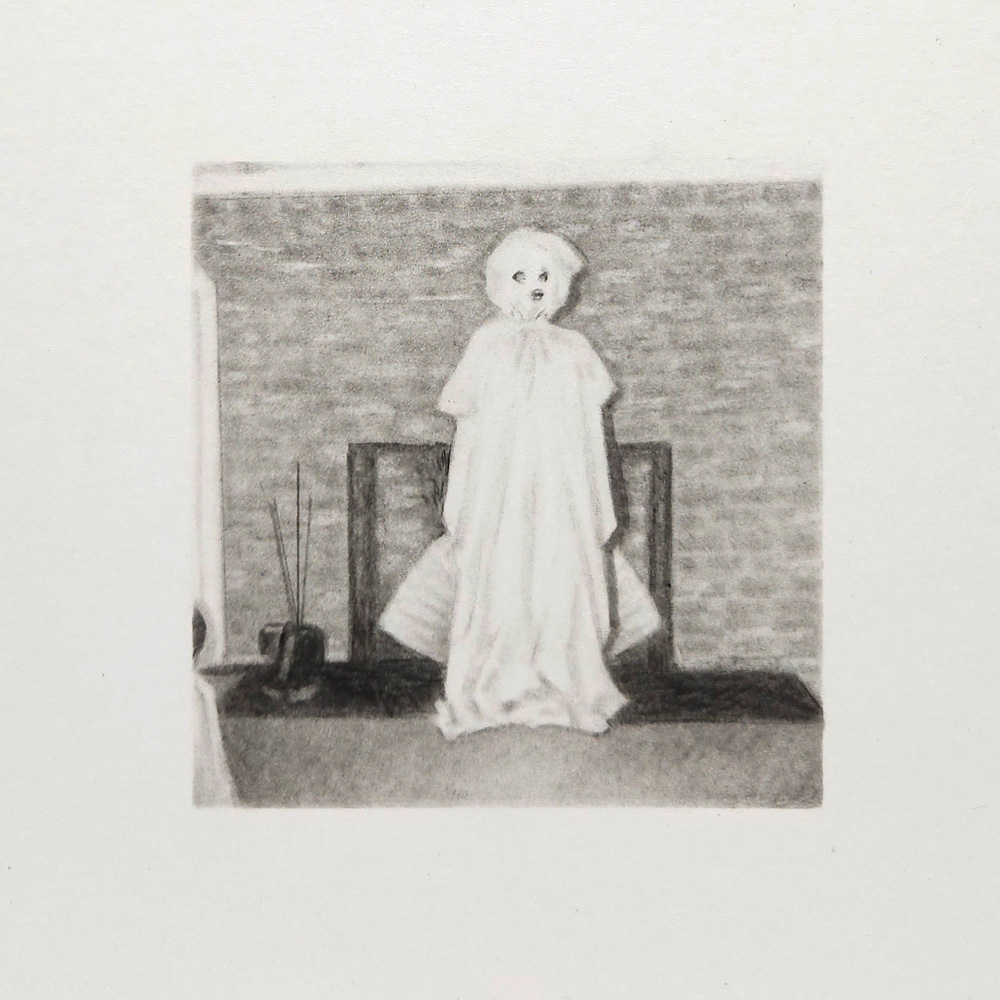

In “Ghost,” three instances of the entity manifest. The first instance lingers within the recollection of a Halloween portrait. The second instance is a chalkboard drawing on paper, where chalk and tangled bundles of pastel compete upon a cramped, heavily worked surface. The final iteration on view is monumental, situated on canvas, with the ghost made prominent upon a fireplace-turned-altar. The identity of this figure is a mystery from piece to piece, and the stature of the entity ebbs and flows with the environment. In one image, the ghost seems to blend in with its initial reference; similarly to the brick and mortar of the fireplace, with edges that soften into each other and reverberate in the graphite translation, so too does the ghoul, a fixture in the living room, an unexpected houseguest that is nonetheless anticipated. Elsewhere, it is nearly dismantled by the caustic surroundings, in danger of being lost all together. Yet, after all that repetition and fuss, the ghost stands alone on the canvas piece, not unlike a pastor sandwiched between pulpit and congregation, between the message and the recipients. This ghost may be a brother, a grim stranger, an omen, no matter. It is derived from prior and drawn into existence so that we might see and, finally, listen.

READ “HAUNTINGLY FAMILIAR” BY WREN FLEMING IN DSM MAGAZINE

VIEW WORKS INCLUDED IN THIS EXHIBIT