TEXT BY MICHAELA MULLIN | VIEW IMAGES

Benjamin Gardner– Where the River Meets the Land | Teo Nguyen—Midwest Landscapes

[…] it disappears as if only a figment of my yearning. // I still search, though […]

–Benjamin Gardner, from his read-along book, the cabin (societyofotherhistories.wordpress.com)

Maybe this is the most disturbing thing we can learn from the ongoing viral epidemics: when nature is attacking us with viruses, it is in a way returning [to] us our own message. The message is: what you did to me, I am now doing to you.

–Slavoj Žižek, from Pandemic! COVID-19 Shakes the World (OR Books, 2020)

In his recent New Yorker essay, “Home Alone Together,” critic and novelist Geoff Dyer writes about our current isolation: “The best we can do is disappear into the great indoors: an unprecedented inversion of everything that has constituted solidarity […]” He talks about (phone) screens also, once the purported enemy of intimacy, and how they are now the necessary connector of people everywhere—offering a slight, and albeit virtual, chance to be intimate with each other. All from inside our respective shelters, in place. And then there’s this phrase, which keeps popping up on social media feeds: “If you think artists are useless, try to spend your quarantine without music, books, poems, movies, paintings, and games.” Yes, try. It is difficult, quite difficult. So, here on offer are Moberg Gallery’s new exhibits with which to visually, intellectually, and emotionally stimulate.

A pandemic such as COVID-19 has been, would be, and will be, I’m sure, a perfectly chilling subject for any arts and science fiction, yet here we are, real live characters in an utterly science non-fiction narrative. Where pre- meets post-, placing us squarely in Now—what some would call apocalyptic. Where the landscape is more unpeopled than ever, due to sheltering in place, and the global concern is the local and vice versa (as it almost always is, but somehow doesn’t register until it affects ‘us’). Well, here we are, all of us. Affected. Potentially infected. And here, thankfully, are the gently stunning new works of Benjamin Gardner and Teo Nguyen, which all of us can view from the dis/comfort of our own homes.

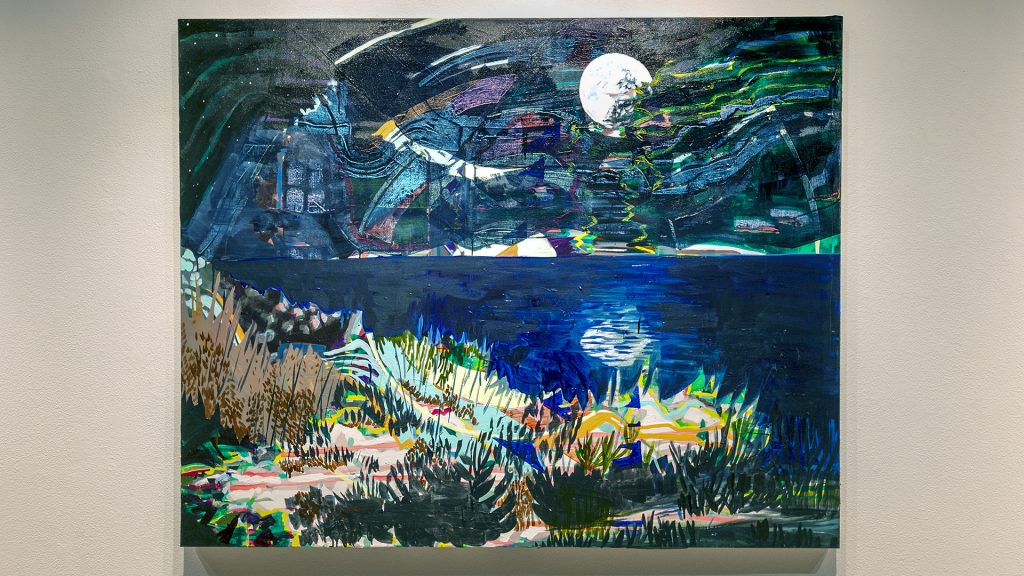

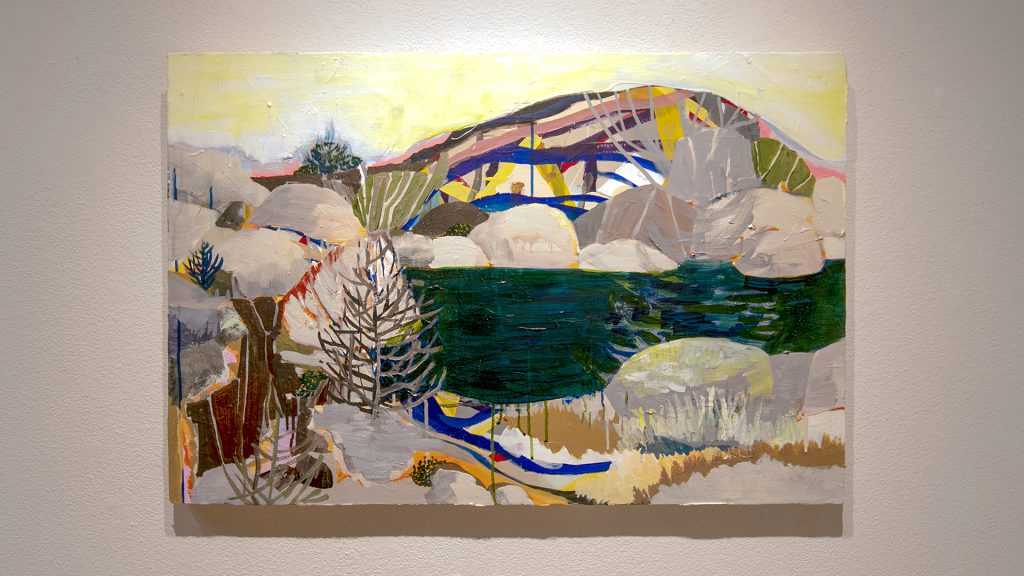

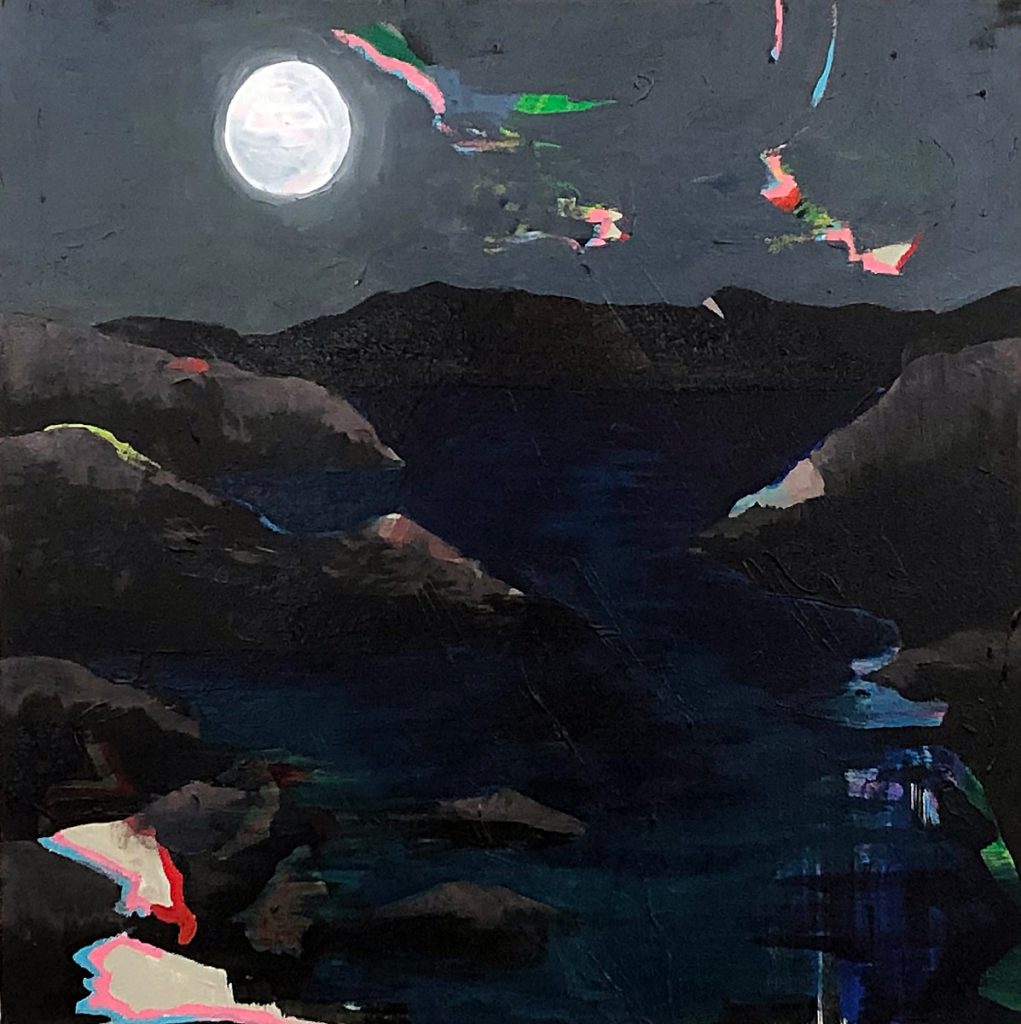

Benjamin Gardner’s artist statement and new work could be read as a portent, a foreshadow—the simple and wise storytelling of what the world is currently experiencing, in some ways, under the acronym COVID. Gardner is concerned with “our collaboration and neglect of the world around us, and the state of after-existence […]” And of this current exhibit, he says, “These paintings are of rivers and lakes and the areas where they meet the land […] Space, color, abstraction, and depth all work to allow the viewer to feel as if they are looking at these places for the first time […] While maintaining some aspects of conventional landscapes, these paintings often include disruptions, invasive species, and spatial abnormalities that reference unseen and complex ecologies. I see my paintings, drawings, films, and books function together to tell stories of impending changes on personal, global, and universal levels.”

Each of Gardner’s paintings can be seen as an advocacy “for the environment in the Anthropocene”—this time period of humans, this Now of which we speak and breath and eat and distance within. When looking at Gardner’s acrylic paintings on canvas, paper, and panel, one finds the delight of nature by way of synthesis, synthetics, synergy—the melding of memory and reality. Ontologically speaking, these works present a new experience for the viewers based on multiple and varied experiences of the artist. The relational elements are perspectival, referential, even haptic—though you cannot touch the art, even in non-COVID-19 times—as they convey a tactile knowledge: a geo-haptic understanding of the land and its protuberances, hill, valleys, wet and dry patches, and destination paths. This result is why it makes perfect sense that Gardner is also interested in sound, (moving) image, and text synthesis as well (buy his read-along book, the cabin http://www.benjaminagardner.com , and watch his videos at https://vimeo.com/user63886877 ).

Imagine construction paper collage, decades-worth of beautifully-layered and removed (or applied as if removed) wallpaper, a book bound by string, a child who knows too much, who imagines the world as unpeopled terrain for discovery—to be the first. Gardner’s work evokes a sense of pioneering—finding/envisioning the shape of every thing by way of an individual view, and then determining shape(s) of the world or universe (or multiverse) by collective. There is a precocity to these works that makes one want to travel in them, meditate on them, explore all that Gardner has been exploring with them—in an effort to learn them, and perchance, ourselves.

The daytime paintings: “Joshua Tree #2,” where the hills appear as an amalgam of pathways, seemingly taped together as an indicator of lines and boundaries that get trodden while crossing. The palette here is desert crisp and dry, yet the black water is collected—a spot of wet in the desert dam, perhaps. “Boozy Creek #1,” creates a version of the waterway that crosses Virginia and Tennessee. The playful colors of pinks and oranges amidst the brown and green all make a visible foundation for the serpentining darkness as it forms the very land that holds it.

“Cotswolds #1” overlays grey to tell a story of this English geography. Water here is reflective like ice, the trees stripped of their leaves, and the pinks and purples peek out from behind the color of frozen water and precipitous atmosphere. Again, hints of yellow flash, perhaps as a reference to limestone from the area, or perhaps to make sun and flesh both a part of the landscape.

“Plane-tree of Stanway,” places us again in a UK space. A haunting of building silhouettes seem to hover in the background, standing above auras, like half-tones, around trees and plinth-like structures. Various blooms and stems in turquoise and lilac pop up from the foreground, reaching toward the foreign shapes in the tree’s branches, in the knolls, and at the line where land meets a body of water.

The painting, “Lost Lake,” positions the viewer to look out over the water, and over the hill, and over the mountain, and over the cloud cast, and into each ecological depth. The white foliage echoes the white of the sky, embracing the land and water and offering stark contrast to the liquid blue and leafy green, and complementing the small pink blossoms on an otherwise bare tree.

“50 Island Water” appears to fall between day and night. Its gray and white, with a hint of yellow in the sky, operates as an upside-down buoy for the mounds and the water, the grasses and shores. Gardner builds the land, air, and water carefully, but with enough intentional imperfection that it feels natural.

The full moon landscapes: “Cold Moon,” a December moon, has sky and water in an almost identical dark icy blue, but the shining of the sphere is seen to illuminate below the surface and show itself twinned on the water’s top. Faraway peaks and ridges twirl into becoming an opening in the sky, and the shores, in white and gray, depict the frosting of the ground and the snow-capping of the season.

“Crow Moon,” which references the last full moon before Spring, is the darkest of Gardner’s work in this show, and fitting, if spring may be considered dawn. The orb radiates its halo enough to catch sight of the objects/species in flight, also beautifully rendered as glimpses of another sky, another dimension, another, an other. The pools at the base of the rocks look of light—the edges and in-betweens, glowing.

The peeking September moon, “Barley Moon,” lights the air and water as they ever so subtly ripple below and make currents above. An extended halation here makes vibrant the lower fore of the painting, as the radiant soil approaches the moonlit lake. In this nightscape, the extreme texture and pattern within shapes reflects a breeze for anyone gazing.

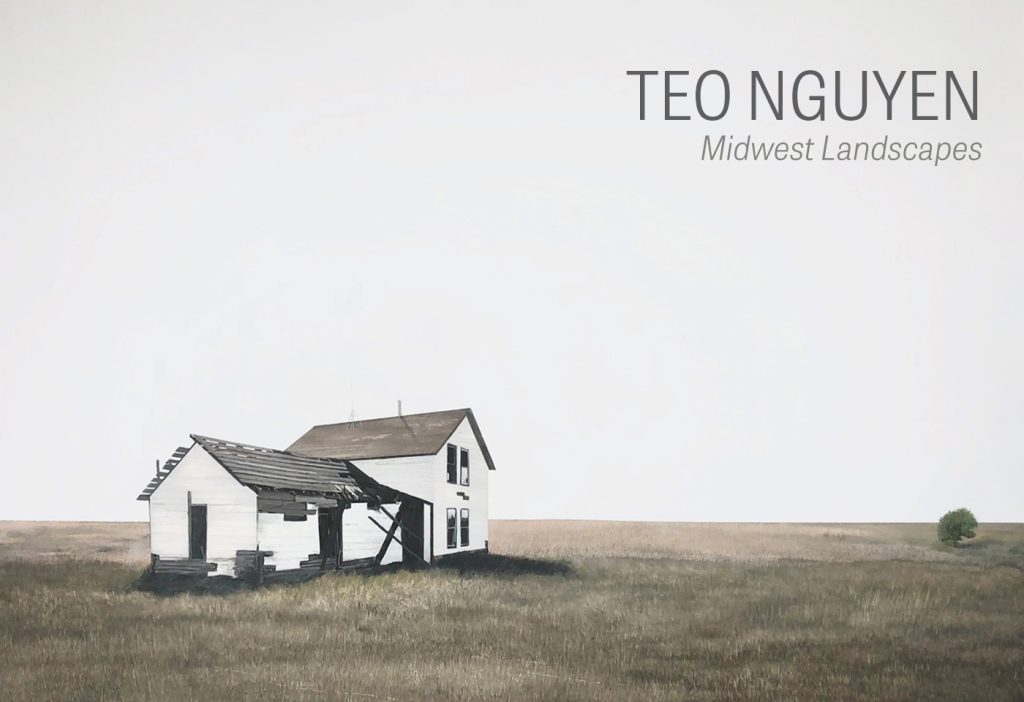

Teo Nguyen

Teo Nguyen’s photorealistic paintings on vellum edify with observation. He says, “These paintings are an interpretation of what I feel and see: moments in which we are alone even as we are connected to each other, connected to each other in our aloneness.” That Nguyen can scenarize solitude is what makes him such a good storyteller. Like Andrew Wyeth (think “Christina’s World,” without Christina, and “Airborne,” once all the feathers have landed), Nguyen, in using the emotion the landscape elicits, manages to imbue a two-dimensional work with a sense of being in a 360-degree space. For an artist who grew up in a fishing village in Vietnam, a place, “where we cast our eyes down,” Nguyen has truly lifted his gaze. Nguyen says, “[…] I am always a stranger to what I see; always slightly outside, finding in what is ordinary to others something tender and strange.” And he is interested in seeing the cultural differences between his country of origin and the spectacle-makers and seers of the United States: “bold-face stares with which Americans confront their surroundings.” With his new paintings, he is searching for the meeting of these two approaches among the Midwest landscape.

In “Midwest Landscapes,” all acrylic on vellum, Nguyen renders isolate dwellings on vastest and flattest land, and by way of his clean-cut horizon lines, this land—with its spare trees, poles and structures— attaches to the largest, most expansive and deep sky. It is spatial parallelism and a meeting of two elements; just as Gardner’s is land to water, Nguyen’s is land to air.

“No 98,”in its horizontal length, holds its sprawl tightly, held by a diffuse and downy cloud cover. The clusters and groves of trees are witnessing subjects to the barn, shed, and silo. Long blades confront the viewer at the bottom edge of the frame, and shorten, getting mowed in perspective. “No 90” , is clear and crisp, with precision focus, where each plank on the dilapidating house is sharply delineated, and the sky is so perfectly even, it looks solid.

“No 91”, is a mostly chilly white square, with the small warmth of browns, of the exposed dry ground and standing barns. In “No 89”, the blue-gray sky meets more here than the eye can actually see—trailers behind walls and fences behind fences. But these views from the road (or the gallery, or the screen), with their oversized skies, narrow strips of land, and indicators of human existence, help us maintain an upward vision, one that extends out great distances, and, with hope, into the future.

For additional information and to purchase works email info@moberggallery.com or visit mobergshop.com

Exhibit Images

Benjamin Gardner