TEXT BY MICHAELA MULLIN | VIEW IMAGES

Dahlquist and Arneson: Between (and Among) Worlds

Moberg Gallery’s new exhibit, Full Circle, with ceramics by David B. Dahlquist and paintings by Wendell Arnseon, creates – relationally, physically, and artistically—just that: a wholeness. A closing. But this fullness is not about ending; it is about the cyclic continuation of and within life. Because to close indicates a next opening.

Curated to create dialogue between the artists and their respective works, the art in Full Circle talks and listens to each other. The works hang interspersed, and opposite, giving the viewer an intermittent absorption, melding works in the memory, and sparking connections.

Gatekeeping, boundaries, divisions—these are thematic lines and borders that exist in both Dahlquist’s and Arneson’s works. Clay and canvas; teacher and student; two and three dimensions; peers and friends—all these pairings, with their inherent individuation, slowly and stunningly come together as one … collaboration.

“Between Worlds” is Dahlquist’s wall sculpture inclusive of the sum of parts, two lines curving out of a full circle—which is to say its interior is full, in addition to linear closure. The leaves, the lines inside what exists outside the bounds of the circle, substantiate the work, inviting you inside. What is so powerful about this work as representative of Dahlquist’s work overall is the invitation. And that this invitation is a portal, which makes inside and outside, and which makes the exterior view an interior experience.

Dahlquist’s haiku “fences,” such as “Color Changing,” “State Fair,” “O. Henry’s Last leaf,” “Snow Fence,” and “Night Sky,” are spare works of different lengths and varied number of lines/panels. However, they are each born from and accompanied by a small poem. Objects that cordon space and land for exclusionary and protectionary measures, fences sometimes make us feel equally proprietary and safe. They are vertical barricades for horizontal movement or trespass. As was August Wilson, who wrote in his play, Fences, “Some people build fences to keep people out and some people build fences to keep people in,” Dahlquist is in constant investigation of the ins and outs of creating stories and where and how points of view tell them differently.

“Zipper” is a deeper circle, its depth creating more circumferential shadows. Within this work are rust-colored leaves, held with linear patterns, parallel curves softening the crispness of the mélange. Like train tracks near fallen nature, the enlarged zipper-like engraving explicitly deals in opposites and fitting, or opposites fitting. “Clear Margin” also has a thicker lip, making of itself an unlikely target, solid yet fragile, heavy yet small, in the scheme of things. The semi-smooth interior of this work then gets ‘undone’ by what appear to be dings, holes that do not go all the way through. One might imagine bullet holes, as the crimson red around these markings lends to thoughts of the residue of violence. Around them is a darkening, as a shot would blacken its target. The emanating circles coupled with dripping glaze evoke a bleeding out of thought that also wants to use the marks as triangulation, and in doing so, somehow captures the essence of this small world.

“How do you draw a line, she asked? Right to left across my heart” and “Fence/Vibration” are quiet works; the former having one line through the circle, creating two unequal spaces of different hues, and the latter being striped in dark variants of blue, brown, gray, and yellow.

“Moving Memory Across the Bridge of Word and Object (for my brother Daniel)” is a circle for his brother, who is a poet. It contains bits of words on strips, zagging to form corners around what appear to be triangles and polygons in greens. Then that expectation is elegantly not met by the outer curve of the circle that barely contains all of this.

Dahlquist’s “Truss,” pulls everything together, holding lines that build a strong titular structure, such as trust. When we design, engineer, create, and communicate, be they houses or homes, families or friendship, the lines that make up our spaces in the world also connect us in them. The lines here extend straight beyond the boundaries of the circle, crossing the outline of the disc. The visual hold offers containment and exploration beyond, simultaneously. The rough edges of the round shape offset the precision of what is diametrical here.

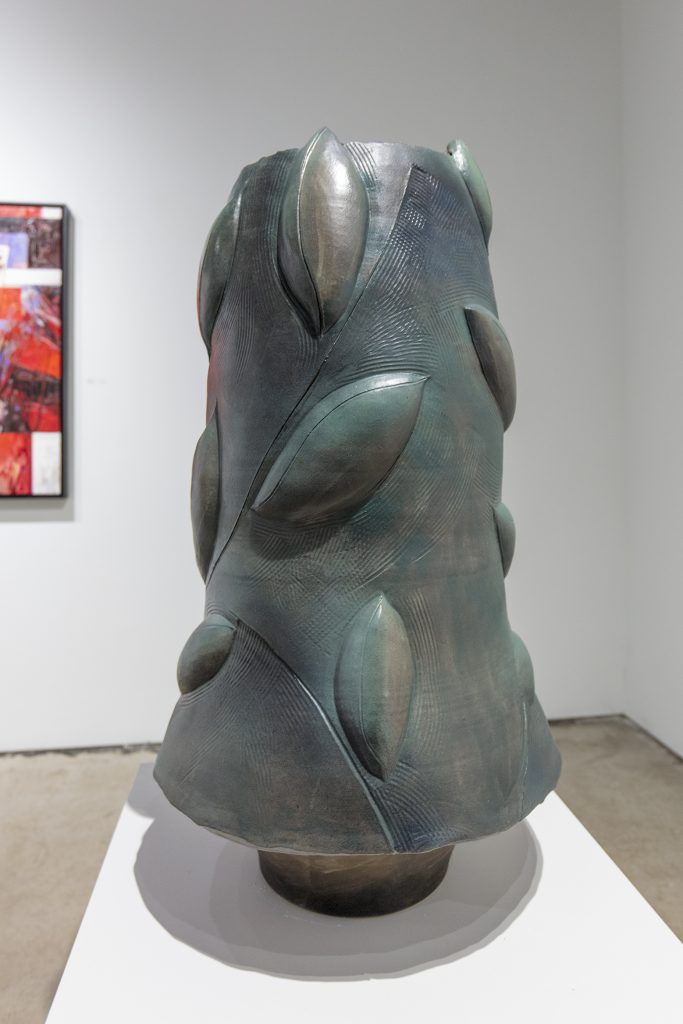

Dahlquist also shows sculptures as vases or urns that ask the viewers to walk around and around them to truly understand their fortified containment by forms that entice. And ceramic masks that hang and haunt on the wall, depicting exhibitions of interiority, in all their expressive complexity.

Wendell Arneson’s painting, “Sunrise,” appears to be rose madder and crimson imagining the original line and circle (as far as human’s can perceive), where the horizon line slowly emerges our solar sphere. “Pond Mapping” uses the rigidity of a grid to “map” the least rigid thing—water. This orderly painting incorporates blue dots placed at the axes, locating a ‘hereness’ that is how we determine ‘there,’ and combines the disorderly environs of a pond area with pale blue drips representative of the liquidity one would imagine. And “Meadow Markings” is a less orderly land painting, but Arneson’s circles, like geodetic markings for surveyors, steady and ground it, so the eye can move and stop, move and stop.

“Dividing Line” is a mixed media painting that clearly delineates the canvas into two lots, and again into a smaller one. There is also a top horizontal line—less clear for division of the work itself, but rather of the subject of the work—that does not meet but misses by slight slippage.

Arneson’s “Spring Creek” series renders different scaping with various palettes and discernable, representative objects such as houses and boats; and the “Gate Keeper” series employs lines and gradient hues to prepare lots–contiguous plots that get connected by overlapping ‘third party’-lines. The titles of this series also add the third party—the viewer— acknowledging the fourth wall in art, which is actually time and space, and therefore is always, thankfully, broken.

“Looking Through” feels like the most integrated—and compositionally culminative—painting, perhaps. Systems appear from the adjacencies of shape and color. With a suffusion of yellow, cut through with red line and situated with a lever-like body of water, the investigative vantage from the viewing virgate (parcel of land that can be ploughed by two oxen) does the amazing telling of a story of more than one. Always more than one.

A few of Arneson’s paintings, in their black-and-white-checked edges, are reminiscent of old negatives or slides. But the entire body of work harkens to holding up memories of place, finding light and seeing through to the other side/s.

Full Circle is up until Thanksgiving weekend. Dahlquist and Arneson’s work commune in the gallery space, giving thanks to each other, and you’ll give thanks, as well, for having viewed these artworks while they can be found together.

Exhibit Images