TEXT BY MICHAELA MULLIN | VIEW IMAGES

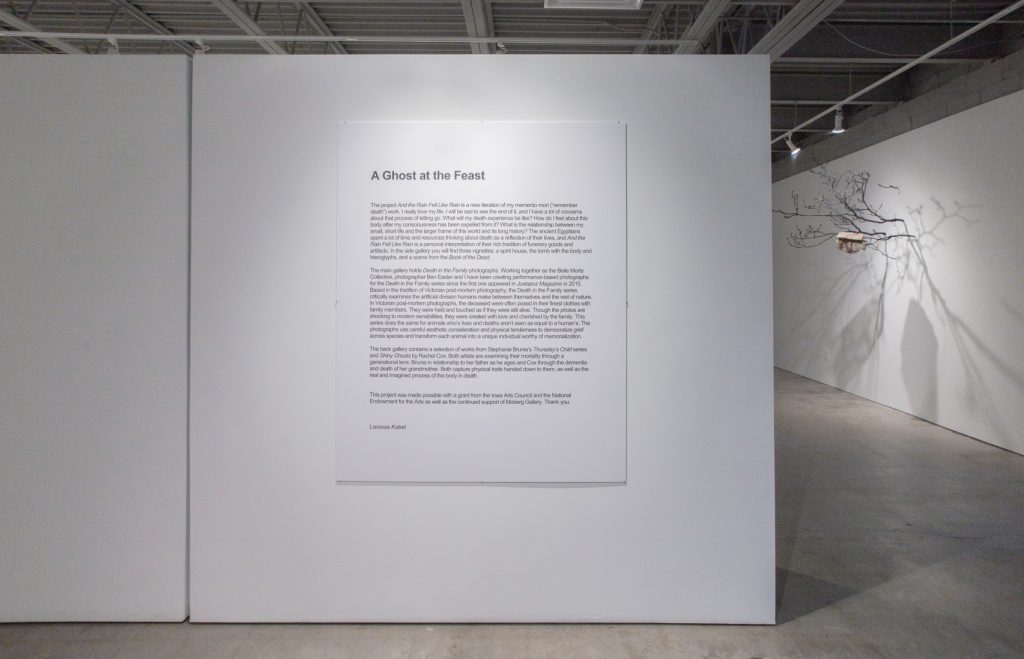

A Ghost at the Feast

Works by Larassa Kabel

Also exhibiting are Mary Jones, Stephanie Brunia and Rachel Cox

A Ghost at the Feast is the echo or shadow of Larassa Kabel’s ongoing art manifesto, indicated through her many mediums. There is a thread (or twine, perhaps) through each sculpture, performance, painting, and drawing. For Kabel it is not about the morbid, but about human processes and ritual—the how of living with love, loss, and survival. And key in how we live is how we experience death. This often interspecific (or inter-special) is not about the taxonomical distance of species but how despite this, the dis/connection is deeply felt and affective.

Art is always about living. And though Kabel’s art is not about clinical pathology, her entire oeuvre does take on human pathos. In her artist’s statement for this exhibit, she writes of the Death in the Family series, twelve vital and tender performance/photographic works in collaboration with Ben Easter, are “based in the tradition of Victorian post-mortem photography, [these] critically examine the artificial division humans make between themselves and the rest of nature. In [Victorian] photographs, the deceased were often posed in their finest clothes with family members. They were held and touched as if they were still alive. Though the photos are shocking to modern sensibilities, they were created with love and cherished by the family. This series does the same for animals whose lives and deaths aren’t seen as equal to a human’s.”

In the series And the Rain Fell Like Rain, Kabel gives her attention to three elements of funerary practices: tombs and the non-Western epitaphic; entry of the soul into paradisical realms; and where spirits live.

Over 100 gouache paintings comprise “The Forest and the Trees” installation. Born from an ongoing obsession with sticks, Kabel acknowledges them as “beautiful forms of natural design [and] easy to compare them to calligraphic lines or kintsugi, veins of gold used to mend Japanese teacups. For this exhibit, they have become hieroglyphs on my tomb.”

These silhouette paintings of sticks harken back to Antebellum South and Victorian periods of time. In an issue of The Washington Post from a few years ago, the curator of prints, drawings, and media arts for the National Portrait Gallery, Asma Naeem, says this of silhouettes: “Silhouettes are everywhere and we don’t really recognize them [she notes the ubiquitous magazine covers of President Trump’s outlined visage and default Facebook profile pictures…] It’s a very powerful, fast way to convey a person, but also to suggest that person is everybody.”[1] The same could be said for Kabel’s paintings—each differently-sized work could represent any stick or leaf or seed head. However, each gorgeous silhouette is specifically its own shape, its own curve and texture. Collected together, they mimic the hieroglyphic carvings of Egyptian walls and tombs—in logographic splendor. The sculpture of a black deer that lays on the floor before the wall of logograms represents the artist, gone from what we can cognitively understand as ‘this place,’ but she is flocked with butterflies, signifying continued life. Somewhere.

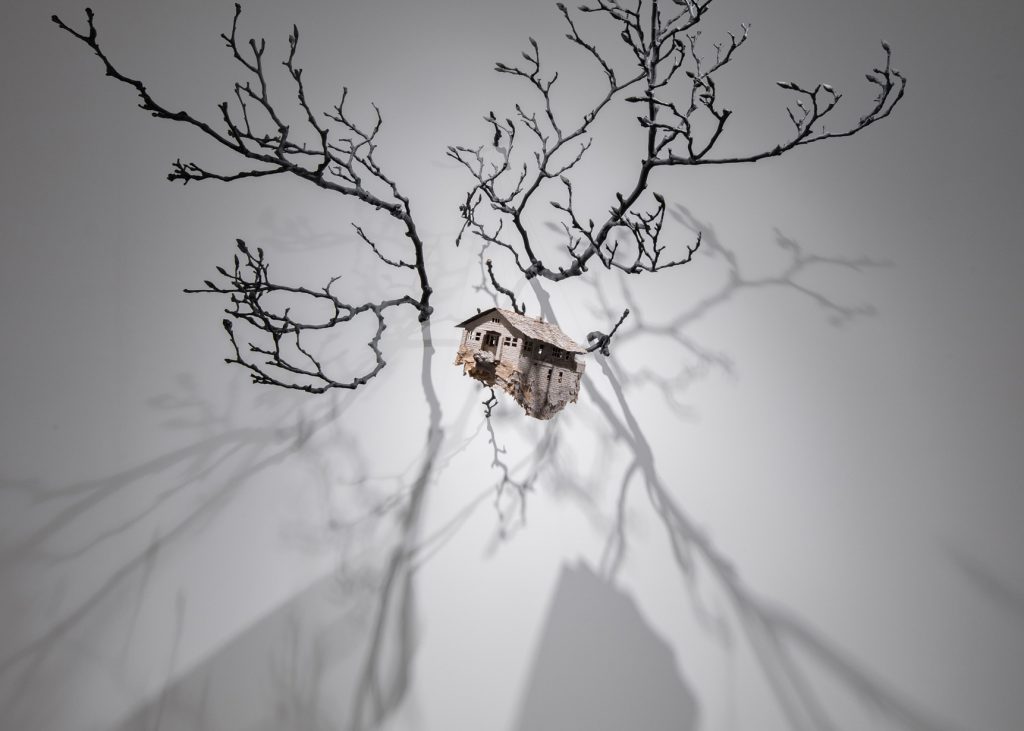

“Spirit House” is a sculptural installation that came about when Kabel realized years ago that “seemingly unrelated cultures had miniature houses” in which souls could live. Kabel’s spirit house is modeled after her own Des Moines home. It is made from wasp nests that had been built on her home and that her husband and son regularly knocked down. She writes, “It seemed poetic and fitting to make my house from the ravages of theirs.”

This house sits in tree branches on the gallery wall. It makes the most mesmerizing shadows. Upon close inspection, its delicate structure and monochrome yet textured architecture is unbelievable in its precision and exactness. Some may think of these nests as now upcycled to the highest degree, but Kabel might disagree. If something must be destroyed, best to make something new from it, but the ‘must be destroyed’ is where Kabel’s thinking originates, questions, snags, releases itself and flourishes.

The trope is that eyes are windows to the soul. But what if on the other side of those windows, sat judges? Kabel writes that, “In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, a deceased person’s soul goes before a panel of 42 judges who decide if it moves forward to paradise […] With this idea and a focus on my relationships, I drew the eyes of 41 people who’ve been significant in my life. The group creates an implied 42nd (and harshest) judge: myself.” These haunting works are so intense, one can almost see what is reflected on the mirror of the eyeball. In the context of this installation, it reflects the artist, but it is interesting to also see what was in front of each subject as they thought of Kabel and captured their soul for her, so to speak, via photographic means.

“42” is, Kabel writes, “a multi-part self-portrait via life review. Using the format of the 18th century “lover’s eye” miniature […] I used graphite on black paper to mimic the dusky view of a Claude glass, the black mirror used by artists to view the landscape, as a way of imagining a deathbed experience. The reflective quality of the graphite means that the drawings can be quite bright or ghostly and almost invisible depending on the light source.”[2]

To complement Kabel’s work and emphasize relationships with the living and the dead, the exhibit also includes stunning photographs by Rachel Cox and Stephanie Brunia. Cox has three works from her series, Shiny Ghost, of and about her relationship to and with her grandmother’s dementia and death; and Brunia’s works, from Thursday’s Child are photographs of herself with her father, about which she writes, “At the core of these portraits is my desire to stave off his inevitable decline.”

Rachel Cox exhibits three works of her grandmother: alive; deceased; and beside Cox, leg to leg, offering inherited shape and form. Cox writes about visiting her during her dementia period, in the monograph of the same name, “She is sitting on her bed, which is now always half made; her side completely in chaos while her late husband’s side remains rigid and neat, a sarcophagus of turquoise Egyptian cotton and frilly shams…her small frame gets lost amongst the menagerie of items tossed on the bed…”[3]

Stephanie Brunia’s works, about a child who “has far to go,” become moments of fortune-telling such as the nursery rhyme suggests, because the fortune we all know will come true is that we will succumb to death. Both born on Thursdays, Brunia writes of her father, “He has been an undeniable fact from the start—his existence seemingly as concrete and fundamental to my world as the laws of physics” And about the fortune we are all told on the day of our birth: “My father’s end is by no means imminent, however, our relationship is clearly facing transition.” “In this work, his flesh is my flesh; and in his finitude, I face my own.”[4]

Two of the three works here are of her father only. One sees him alone in bed, fully clothed, in a horizontal dance perhaps, or wrestling the air with a nuanced lift that conjures quiet exorcism. The other captures him submerged in water, but for his face. Baptismal? Are we all Ophelia in some way? The third photograph includes her. Brunia and her father are face to face, eyes closed in love and comfort. The shot is a closeup; there is nothing in the frame but them.

Mary Jones’ The Map Room installation is lit by northern light at the back of the gallery. With a focus on the urban land and mindscape, as well as a collaborative artist book project with poet Michaela Mullin about the geography of dementia. These works compel you to read maps, space, and our time in the world with a changed eye. A map room is a space to ‘read’ the maps as the stories of their authors. Jones has walled off space within space to create an intimate room for searching and researching movements she has imagined and created.

“Walking was the first notion of freedom I felt as a very young child […] Later, I was bound by someone else’s idea of where I should walk.” This observation by artist Mary Jones is such a surprisingly accurate explanation of her work—a delirious mix of dis/order and dis/assembling.

The central figure in each work becomes the core from which everything radiates, though less within a geographical radius than a mental radius. Using gridded paper of different-sizes, slivers of published maps, photos, text, architectural and figurative drawings, Jones’ allows her intuition about what to include guide her in “the way that thoughts bubble up while walking.” Images and words that make the cut create an interactivity, merging as reimagined traffic, offering new routes for the viewer.

The exhibit ends July 31st. Make sure to include Moberg Gallery on your route soon. Whether it is on your beaten path or not.

[1] Berg, Miriam. The Washington Post, May 10, 2018:

[2] Kabel, Larassa. https://www.larassakabel.art/42.html

[3] Cox, Rachel. Shiny Ghost, Aint-Bad (2016).

[4] Brunia, Stephanie. Thursday’s Child, Times Club Editions at Prairie Lights Books, Iowa City (2016).