Kicking Abstract & Taking Names, curated by Conn Ryder, is an exhibit showcasing the work of a hand-picked group of female painters from the U.S. and abroad, who actively honor and advance the abstract movement still popular in the contemporary art market. These women have forged ahead in a competitive environment through the strength of their paintings, which give voice to the individual interpretations of their uniquely feminine experiences, explorations, and perceptions.

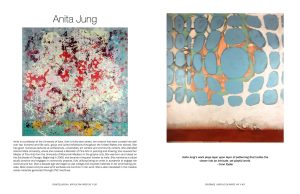

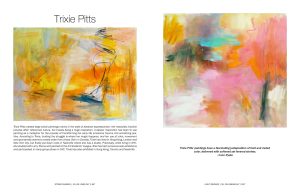

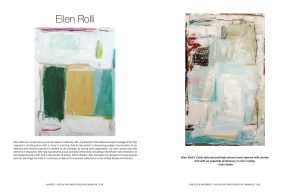

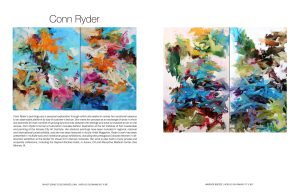

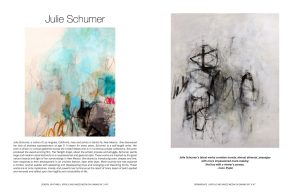

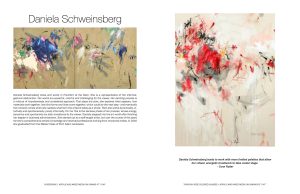

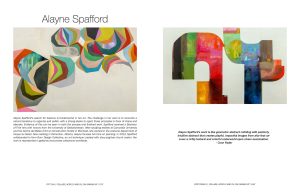

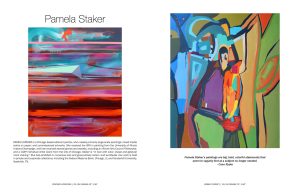

With echoes and whispers, and glorious hauntings, of Hilma af Klint, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning and more, Kicking Abstract & Taking Namesgathers thirteen contemporary artists. But rather than curatorially or individually playing it safe, the exhibit revels in the understanding that there is power in numbers. Included in the show are Johanne Brouillette, Margaret Fitzgerald, Sarah Grant, Dana James, Anita Jung, Ellen Rolli, Conn Ryder, Karen Scharer, Julie Schumer, Daniela Schweinsberg, Pamela Staker, Alayne Spafford, and Trixie Pitts.

Given the wave of women in abstract painting that this century is experiencing, and with the 2016 exhibition (see Ryder reference in the interview below) that helped further the long overdue exposure and recognition of the last century’s unsung painting heroines, Conn Ryder’s Kicking Abstract & Taking Names is importantly timed. There is currently an exhibit, also, at the San Diego Museum of Art, Abstract Revolution, with the tagline, “Women Who Empowered a Movement,” (through February of 2020).

Ryder and the other artists included in this Moberg Gallery show continue the movement(s), continue to become more empowered, to take names, so to speak, and in doing so, to make namesfor themselves. A future where invoking the names of women artists won’t require use of their given names; where surnames will, like for the mid-twentieth-century male artists (and before and after), be all that is needed to evoke a work, a reputation, a place in history.

I was able to email with Ryder to get her take on contemporary abstract work by women in today’s art world, and to gain more insight into her own personal story, her work, and her curatorial prowess, which is elegantly waged as social and political commentary—beautiful communing of line and color as essay or collective missive.

M: The exhibit and title itself, Kicking Abstract & Taking Names, is a direct comment on the history of abstract painting. Historically, the great women abstract artists have been in the shadows of male abstract artists, and all have received recognition far too late. Aside from visibility itself—being exhibited, calling out what and who the art and artists are, and how they fit into the art historical narrative—what immediate take-aways are you hoping for from the show?

R: The groundbreaking exhibition Women of Abstract Expressionism that opened at the Denver Art Museum in the summer of 2016, and traveled to other major museums throughout 2017, showcased female abstract expressionist artists from the mid-twentieth-century, who by all rights should be every bit the household names of the likes of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline or Mark Rothko. Though efforts have been made for decades (the Guerrilla Girls come to mind) to call out the gender bias that has long existed in the art world, it appeared that on the heels of that exhibition, headway has been made toward correcting the imbalance of male to female contemporary artists represented in galleries and featured in art exhibitions. And this year in particular, I’ve noticed numerous commercial galleries and online entities mounting more localized exhibitions focused on women artists.

Because abstract art is an umbrella movement encompassing countless sub-movements, expressed in all forms of artistic disciplines, I wanted to narrow the scope to showcase two-dimensional abstract art created by a small group of emerging to mid-career female painters whose work commands attention in the highly competitive art market, and who deserve to be applauded.

M: Can you talk about this particular group of artists for the exhibit? Why do their individual works, and perhaps the way they create, speak to the thematic thread of the show, and as a group, what kind of impact are you hoping for, that may differ from, say, a solo exhibit of abstract works by any of the included artists?

R:The collective power of the exhibition comes from the stylistic diversity of this cross-section of working contemporary women abstract painters. The artists in this show were already on my radar, largely through social media and other art venues, but also within Moberg Gallery’s own roster of artists. The commonality of the women is that they all have created a body of abstract work with a vibrant and distinctive voice that epitomizes the imaginative and innovative contributions women bring to the table in this tradition.I want Kicking Abstract and Taking Names to celebrate and exemplify the diverse feminine take these women and so many other female artists are contributing to the tradition of abstract painting.

M: In your curatorial statement, you use the phrase “actively honor and advance the abstract movement still popular in the contemporary art market.” More generally, outside the gender basis, can you expand on this?

R: For the most part, what many of us know as abstract art, with all its –isms and incarnations, was born of the modern art era and has continued to endure through decades of contemporary art. And there is still an ongoing appreciation and demand for contemporary abstract painting. I think I can safely speak on behalf of the other artists in this exhibition that we have been inspired by the abstract artists that pioneered the movement, that abstraction as a form of expression rings true for us and that in the same way original music is continuously born out of a limited set of musical notes, we strive to utilize the painting mediums available to us today, combined with our own stories, perceptions and interpretations to create abstract art that is fresh, tells our own unique stories and that speaks to the viewer.

M: It seems you aren’t the only painter in the exhibit with a background in fashion. Does your training as a fashion illustrator inform your mark making and your overall sense of movement on the canvas? Fashion is literally about the body’s exterior (though certainly an expression of an interior); and you say, “Abstract painting is a personal exploration … you turn [yourself] inside out.” Your work is concerned with visual translations of your emotions. In this form of genuine communication, and since your process is so in tune with your inside world, how might of the external world, or the imagined audience, influence the formal elements of the pieces?

R:I was 17 years old when I studied fashion illustration (and dropped out) and am now just shy of 62. So aside from some art basics like color theory, I don’t feel that particular training does inform my paintings now, other than to be another ingredient in the stock pot soup that has been my life. I then largely abandoned art while teaching ballroom dancing, bartending and even doing small aircraft detailing before going back to school in my mid-twenties. After taking art classes while at a junior college, I transferred to the painting program at the Kansas City Art Institute. However, I also dropped out of KCAI because I felt I had missed some important first steps of art instruction. I likened it to someone asking me to write a novel, but I hadn’t learned to construct a sentence.

What followed was a self-guided course of instruction, focusing on realistic still lifes and portraiture. That endeavor eventually took a back seat to relationships and other aspects of my life, although I continued to paint. By age 50, I realized I wanted to bring painting back to the forefront of my life and more importantly to paint for myself, which meant abstract painting. I decided to switch from using the oil paints I had used, to acrylics, and embarked on a long learning curve of how to manipulate these. I’d reached a point in life where I knew I had learned to “construct the sentences” to produce that visual novel I felt I was asked to write decades earlier. What informs my work is that unconventional course of art study, in varying art styles and practice, fused with the equally nontraditional trajectory of my life experiences.

When I say I’m turning the inside out, I try to get out of my own way when I paint – to keep the conscious thinking to a minimum and to, in a sense, go on autopilot and trust that what has been learned and felt and experienced comes to the fore. All that is external (people, places, events) impacts what is internalized. But as I write in my artist statement, my work is brought forth by internally assimilating and outwardly fashioning the emotional response to the experiences, observations and backdrop of my life.

M:I have to ask about your kick ass titles! You often inject such humor into them, thereby adding a levity to the work that may not otherwise be immediately perceived. Can you talk a little about the titling process? How you land on them; do you have something in mind when you begin a painting?

R:Generally, the painting is created without forethought to any meaning, and then I title the painting after it’s been completed by trying to match a title to the feel of the painting.

Some titles are just wordplay that may give hints of my inner nature (or someone else’s). Some are lines or phrases that amuse me and probably sum up some recent thoughts or feelings. Other titles are responses to someone or something that I probably can’t verbalize without repercussions. So, putting it out there in a non-confrontational way provides a level of satisfaction.

When I was attending art school, I coined a term for the uber-serious-posturing of many classmates: the “profounder than thou complex.” I thought it odd that it seemed there was no place for humor. In fact, I began second-guessing myself as an artist because I thought maybe I wasn’t deep, serious or intellectual enough to be a true artist. It wasn’t until much later that I realized there is no one-size-fits-all description of what or who an artist is, or how or where their inspiration and process come from. While I wholeheartedly believe all of the arts are important to society, I’m not curing diseases here . . . and even if I am sometimes drawing on darker elements of experiences and emotion, what’s wrong with lightening it up a little? Besides, it’s a truer reflection of how I personally navigate life.

The title of one of my series, and a painting in that series, “Renegade Spinster,” best describes me, I think. Don’t be fooled by the mild-mannered exterior, because there has always been a rebellious spirit inside, with a lot of humor, a pinch of cynicism, and a dollop of smart-assiness (and, yes, I just made up that word).

M: The two diptychs in Kicking Abstract & Taking Names have great titles, as well: “I’m Not Going to Be IGNORED, Dan,” and “Warrior Breeze.” These two are very different from each other, tonally, however. The specificity of the former makes it feel personal, truly YOURS. In this way, it seems even easier to connect with the painting. Can you talk more specifically about the titling of these two works?

R:The title “I’m Not Going to Be IGNORED, Dan!” was the exception to the rule in which I had the title in mind as I started the painting. The line is a direct steal from the movie “Fatal Attraction” that I’d re-watched recently. Concurrent to that, I felt I’d been slighted by someone, so when the line was delivered so memorably in the movie, it stuck out, rang true, and I thought it was really funny. For me, the title has nothing to do with attractions (fatal or otherwise), and the name Dan becomes nothing more than a placeholder. It only occurred to me later that not only did the title aptly describe what went through my mind after being slighted, but that in a broader sense it exemplified the intent behind the exhibition as well.

“Warrior Breeze” falls more into the category of wordplay; it fits the feeling of the diptych because the color palette overall is cool and doesn’t alone evoke any particular declaration, but the strokes of paint do. Them’s fightin’ strokes! So, the title, too, transcends my own personal attachment to more broadly fit the exhibition, as we female artists soldier forward establishing our place in the art scene.