TEXT BY MICHAELA MULLIN | VIEW IMAGES

Inter/national Contemporaries

These magnificent seven artists, whose works complement the intricately balanced ink and acrylic paintings of Zheng Lianjie, will also be on view until June 15th.

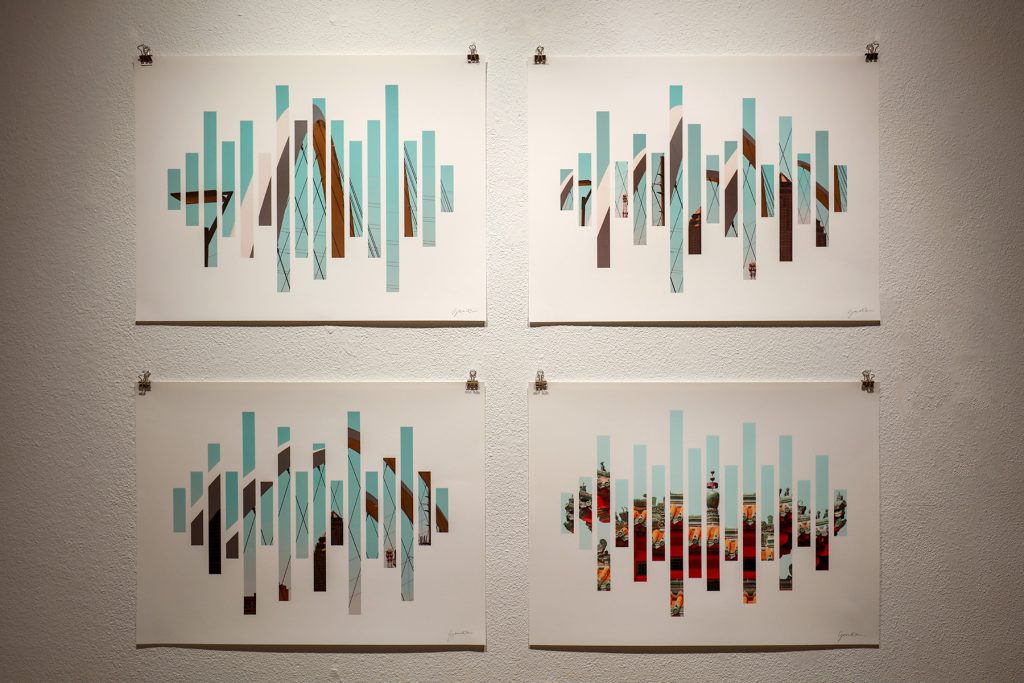

Goizane Esain’s “DSM Bridges #2-4” and “DSM Pagoda” slice series (all C-prints) are more abstracted than her earlier photographic works. Esain wanted her new pieces to be more interactive, relying on the viewer to act as “a bigger player in the interpretation of the pieces.” Inspired by Brutalist architecture, and wanting to deconstruct in the hope that, though less realistic, recognizability ultimately still exists here for the viewer. She says she is “fascinated by design elements found in architecture and the relationship with its surroundings and the sky.” Choosing the Des Moines Bridge District for these very reasons, including the pagoda, Esain wanted to “showcase [the] diversity in our community.” “DSM Bridges #1,” dye sublimation on aluminum, highlights her more traditional processes, reordering parts, though the ultimate puzzle may more quickly to come into focus.

The steel and suspension of the bridges in Esain’s works hangs perfectly next to Miami-based Argentinian artist Carolina Sardi’s “Red”, a dotted installation in painted steel. “Red” takes over and hovers just off an entire back wall of the gallery, each organic oval or kidney-shape creating and doubling shadows. Together, each part makes what appears to be a taking of flight form, the shiny patina creating small reflections of light, adding to the collective shape becoming a part of the whole systemic form. A handful of outlier pieces seem to climb up and drip down from the core cluster, and with the flight standing out, just so, in the third dimension, it both takes leave of and also remains in the normal wall viewing space. The vibrancy of the passion color, the color of arrest and cessation, together make and hold its inherent tension.

Tension, which exists in all good art, exists in the extreme, as well as sometimes in extremis, in the work of Argentinian artist Mariela Yeregui, who resides in Buenos Aires. Yeregui makes artworks that attempt to relay the essence of tensions, or that embody the complex and often intrinsic nature of such conflicts. Her photo, “Amasijo (Entaglement)” is one such work from a larger project dealing with “the concept of disaster and how disaster could be visually represented.” More explicitly, it deals with the body and disaster, which Yeregui states has a close relationship in the Latin-American social imagination. It is a relationship, she says, “based on the absence/presence tension [because] bodies are visible; they populate the space of fiction, of communication, of thought, of art and of poetry.” The “ubiquitous bodies populate” Yeregui’s memory, having lived through the guerra sucia, a period of military dictatorship in Argentina that led to tens of thousands of “disappeared” victims. With her projects, the disappeared appear, “shaping her personal imagery.”

In Yeregui’s pencil drawings, from the “Analytical Views” series, she addresses the tension “between dystopian and utopian dimensions, [thereby] reflecting the […] dismantling of the preconceived ideals of perfect worlds.” Her ink drawings are “fast and free lines that play around the concept of language and systems.” The lines build up, darkening, but overall, make dense spots on an otherwise unpopulated page. White space and heavy ink or graphite mix with more delicate singular lines or water spots, making surreal and almost petri-dish-like growths on paper—systems that expand and confine.

For systems have parameters and as such, also internally enforce them. Tibi Chelcea’s nine “PCG Drawings | Circuit Boards,” made of FR-4, copper, solder mask, and solder are small fabricated circuit boards—a science fiction of sorts. Here, the Enlightenment mind crosses creative paths with art, the circuitry of which makes this two dimensional (bordering on the third, with the fourth in mind) and offline connectivity some of the finest of Chelcea’s prolific board-related pieces—and in his prolificity, he may have come up with a new constructivism for the digital age.

Georgi Andonov, however, paints with a focus on the historical analogue in “Chantilly,” “Beloved,” and the fabulous “Nocturnes.” Andonov wants to paint beautiful things and joyful scenes, and admits that in his work, he is longing for “romantic nostalgia.” His belief in “the distillation of reality” and the humor with which he infuses his oil paintings creates a perfect tension between the perfectly dark and perfectly colorful analogies of night hauntings and gorgeous sun settings. All of this wrapped in Baroque and Rococo fairy tale scenes—all three large-scale paintings of a couple—a coral-suffused homage to an age of reason.

Andonov’s “Owl” on the other hand, perched upon nothing, is an extravagant bachelor, floating, though not flying, on the canvas; its background, gradations of gray. This nocturnal bird of silent flight is majestic, the feathers here bright oranges and indigo, with gold and white to offset the beak that implies predation or sound. And in that ambiguity, the sound of predation, like the sound of the mandolin in “Nocturnes,” comes echoing out of Andonov’s imagination.

Annick Ibsen’s ceramic sculptures and mixed media paintings, “The Lovers,” are also of coupling, an abstracted Cubist coming together. Ibsen’s new works here are color composites as well as portrait/imagistic composites of shapes. The browns, reds, yellows and blacks ground what may otherwise feel too Futuristic for the gentle slowness, or a tenderness not often found in Cubism, of her work. The doubling of the two- and three-dimensional works, in both “Cubist Nude” and “The Lovers,” renditions of each other, also highlights the twinning of human connection. The lover is also the complement. The embracer is, by enactment, the embraced.

But while doubling may seem to be about balance, Yin and Yang, per se, multiplying or proliferative growth leads primarily to the main subject of the four oil paintings by Juan Manuel Arreaza, from his Overload series. These scenes from the streets of his home country, Colombia, are small. They are small pictures of people and things, people doing things, such as standing, riding a motor bike or a jeep, pushing a cart. And on these people or bikes or in these carts are jerry cans, carboard, balloons—or just more people riding a jeep. The paintings are miniatures on larger panels and canvases, miniatures within a larger open “empty” space. And in taking a distanced look, it is clear much is happening, overload is happening within the cluster of the central image, even its attached shadow. The details are not all sharp, however. The blur deceives us, giving the viewer enough form that we think we discern clearly what is only implied by the huddle or the crowd. Arreaza masters the appearance of a scene by disappearing its external locative case; by allowing the overload to be beautifully contained, and carried, for a moment.

Click to view Exhibit Documentation for Zheng Lianjie | The Line is the Beauty

Exhibit Images

Click to view Exhibit Documentation for Zheng Lianjie | The Line is the Beauty