Annick Ibsen’s Algebraic Dignitaries + The Architecture of the Body | Text by Michaela Mullin

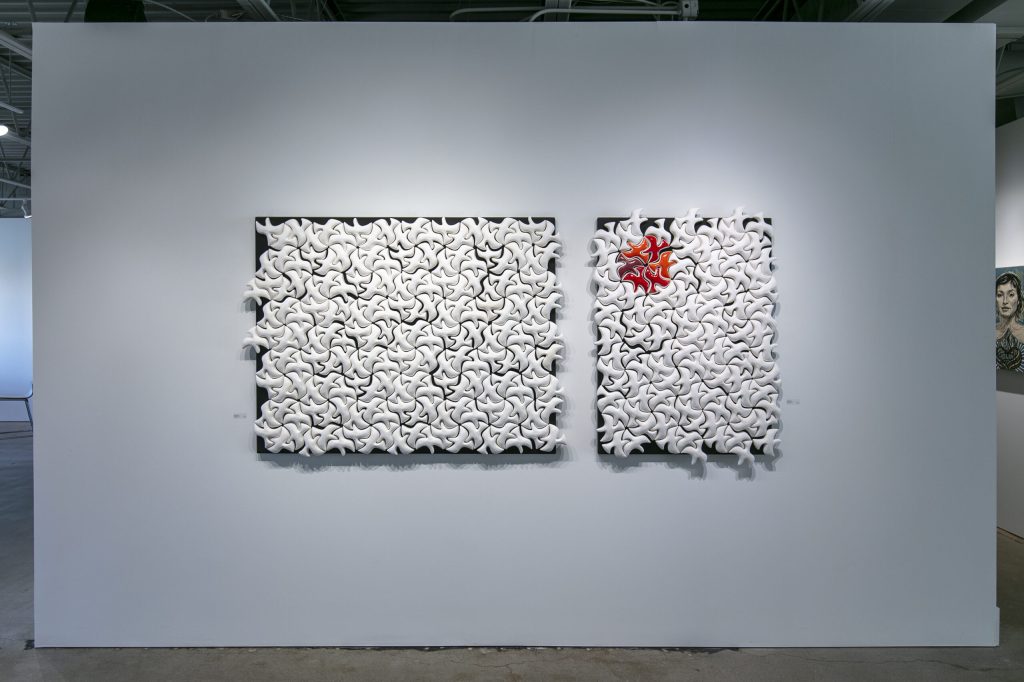

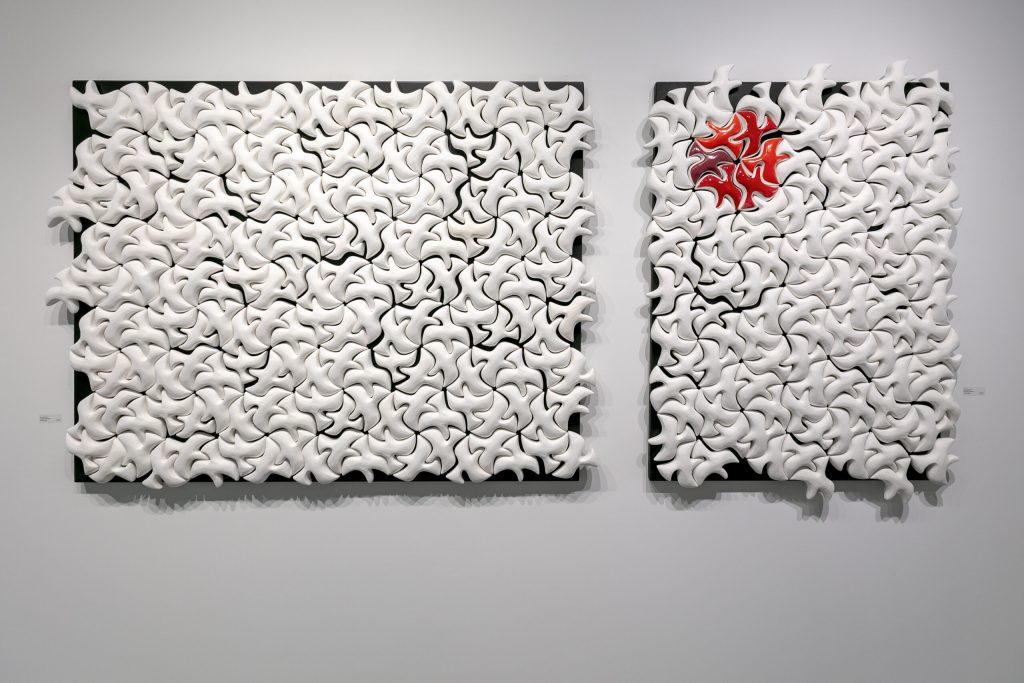

Annick Ibsen began work on the “Murmuration” project pre-pandemic, in the Fall of 2019, and it “turned out to be timely.” Not just for the time and focus permitted due to quarantine, but also in the investigative elements re: social relations and intentions. This was the first large-scale project where she “had to create a perfectly geometric shape that would embed itself infinitely.” The repetition and its monochrome white juxtapose the maximal and minimal. And the level of technical precision required was great. It took more than a year to complete this tessellated work, featuring hundreds of the same bird shape (one of Ibsen’s signature forms)—a “ceramic mural” at 7’ x 4’.

Each piece was made using ‘slip casting.’ This, paired with the clay’s weight, was one more challenge in her ongoing attempt to create lighter sculptural works which can hang safely on the wall. Beyond the practical, however, Ibsen notes that, “such a tight formation raises questions of individuality versus group responsibility, how the behavior of one can affect the rest…” Each piece, of course, is slightly different; the impossibility of perfection and perfect replication allows for nuanced change, imperceptible at a distance. For distance is such a cultural motif today, and Ibsen recognizes that when distant, “the crowd seems harmonious […] but each bird flies in a different direction from its neighbor.” In order to make the puzzle work, it must be this way. The ‘fitting’ and modularity offer room for movement and holding. Reconfiguring becomes the law of the sky.

***

There is nothing primary or basic, in general terms, about Ibsen’s “Three Kandinsky Nudes.” These homages to Wassily Kandinsky, however, do take up Bauhaus ideas of geometric shapes and color: Yellow triangle, Blue circle, Red square. Ibsen renders the human figure in these “inferred” forms, but with Kandinsky’s warnings in mind—that radical abstraction risks creating geometric ornament, to which Ibsen victoriously says, “I think here I proved [Kandinsky’s] point; I abstracted without negating.” This project began as an academic exercise, Ibsen notes, which she says offered an unexpected turn when she began addressing the color component to the figurative shape/sculptures. She uses acrylic and felt beneath the sitting figures to “hint” at the equivalent hue for each position.

These new works sit perfectly within Ibsen’s personal oeuvre, with its quandary or unease about the term “abstract art.” It is a dubious term that mandates a perceptual origin, which of course then throws every other term and ‘ism’ into question. She says, “I totally agree with Kandinsky’s conclusion: Realism=abstraction; Abstraction=realism.” Ibsen knows, however, that an investigation is never complete or over, so she keeps researching and exploring. The world is fortunate to view her process and culminations, from any distance.